Sing, sang, sung and other linguistic fossils

A history of English “strong verbs”

What’s the past tense of dive? Dived? Dove?

Depending on where you’re from — and maybe what mood you’re in — you’ll have a different answer. For you, dive might work like arrive (past tense arrived) or like drive (past tense drove).

How about this one: what is the past tense of sneak? Is it sneaked or snuck?1

The debates about these forms point to a tension that has been tugging at the English language (and its ancestors) for over two thousand years: two competing systems for expressing the past tense of verbs, one nice and regular (-ed) and the other… not so much.

Today, we’re going to be talking about verbs which are less well-behaved. These are verbs like sing, give, drive, and speak, verbs whose vowels change between the present and the past tense.

So today I sing, give, drive, and speak, but yesterday I sang, gave, drove, and spoke.

And when we go to form the past participle of these verbs, we see yet more vowel changes, and sometimes even a new suffix -en: You sing a song, give a gift, drive a car, and speak a language, but the song was sung, the gift was given, the car was driven, and the language was spoken.

These are the so-called strong verbs of English. They aren’t the only irregular verbs in the English language, but they’re a relatively large group (just under 100) of mostly common verbs, and the patterns they show are a big part of what makes English feel like English.

In fact, these strong verb patterns seem to have a life of their own: the existence of sing, sang, sung tempts us to say bring, brang, brung.2 Ditto sink, sank, sunk and think, thank, thunk.

I confess that, in a moment of enthusiasm, I too have conjugated arrive (arrove, arriven) on the model of drive, drove, driven.

Where does this strange verbal behaviour come from? This is our topic for today: the history of English strong verbs. It’s going to be a wild ride, because, as it turns out, this little quirk of certain English verbs unlocks the principle by which the most ancient ancestor of English functioned.

You're reading The Dead Language Society. I'm Colin Gorrie, linguist, ancient language teacher, and your guide through the history of the English language and its relatives.

Subscribe for a free issue every Wednesday, or upgrade to support my mission of bringing historical linguistics out of the ivory tower and receive two extra Saturday deep-dives per month.

If you upgrade, you’ll also be able to join our ongoing Beowulf Book Club. You can also catch up by watching our discussion of the first 915 lines (part 1, part 2, part 3) right away.

Used verb system, condition: fair

But before we travel back into prehistoric times, allow me to explain how the strong verb system worked when it was at its height.

Our story, therefore, begins back in Old English times (AD 450–1100), the period in the history of the English language when the system of strong verbs was at its, well, strongest.

Old English had many more strong verbs than Modern English does, around 300 all told, if you exclude compounds. We’ll discuss why the number has gone down later on.

Almost all of the Modern English strong verbs are readily identifiable in Old English. Let’s take an example of a familiar verb: drive. We saw above that drive has three forms in Modern English: drive, drove, driven.

We call these three forms the principal parts of the verb. What that means is that they are the only forms you need to know to be able to use the verb. But if you lacked any one of these three parts, you wouldn’t be able to form it from the others.

In English, the principal parts of a strong verb are: (1) the bare form of the verb, e.g., drive; (2) the past tense, e.g., drove; and the past participle, e.g. driven. So too for the other strong verbs, e.g., sing, sang, sung; speak, spoke, spoken; give, gave, given, and so on.

Old English strong verbs worked similarly, but had an additional wrinkle. Because Old English had a more elaborate system of verb conjugations than Modern English does, Old English strong verbs required four principal parts rather than three.

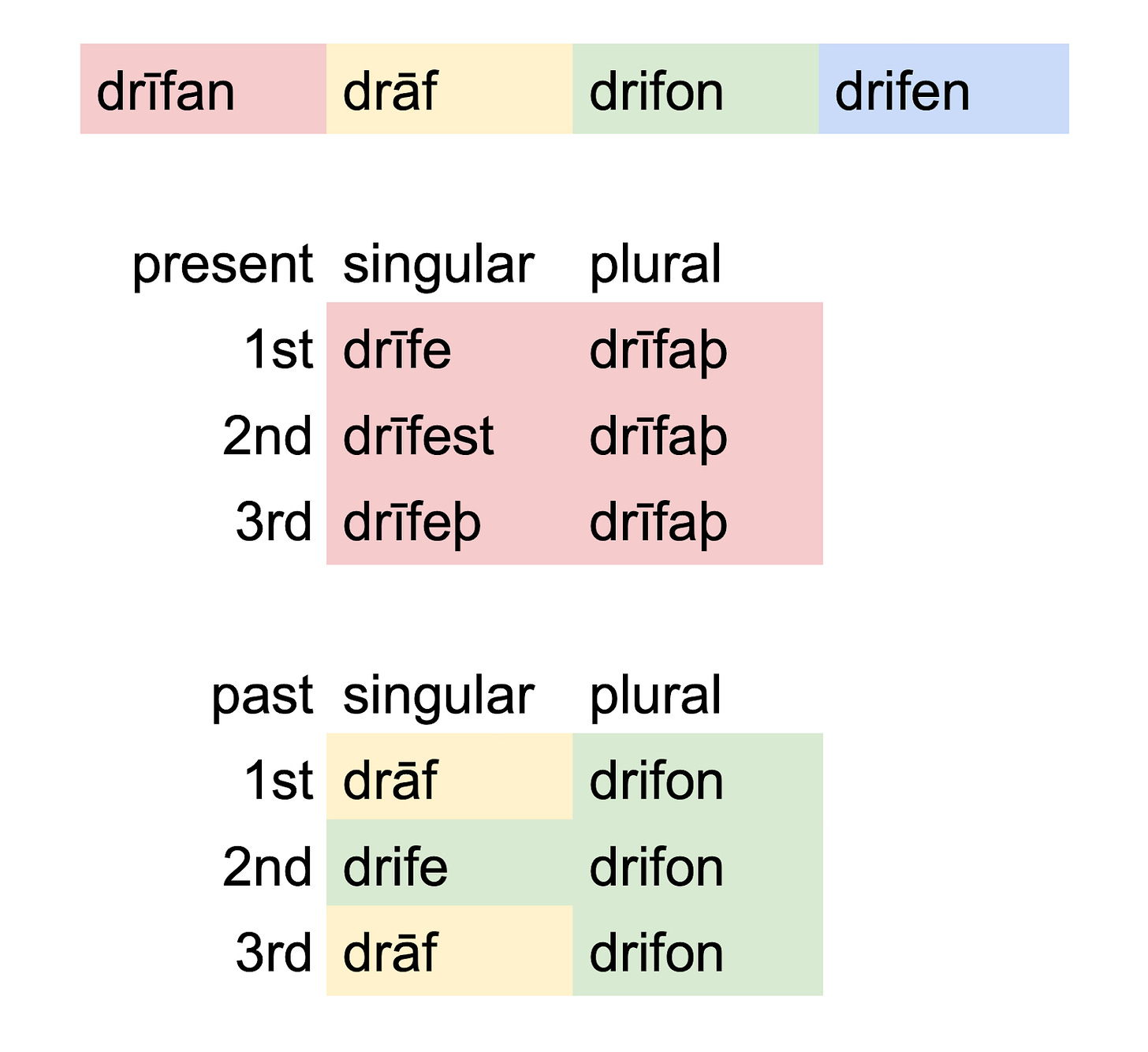

Let’s take the ancestor of drive as our example: Old English drīfan.

Drīfan ‘to drive’ has the four principal parts drīfan (the infinitive), drāf (one past tense form), drifon (another past tense form), and drifen (the past participle).3 The first and the last of these principal parts work the same as they do in Modern English: the first principal part lets you form the present tense of the verb, while the last is simply the past participle.

The reason for the extra part in the middle has to do with the nature of Old English grammar. While Modern English has one past tense form that suffices for everyone: I drove, you drove, he/she/it drove, we drove, they drove, Old English verbs change a bit in the past tense.

Strong verbs use different vowels in their past tense stem, depending on who it was that did the verb-ing. That is, depending on the person and number of the subject of the verb.4

For example, here’s drīfan in all its glory, colour-coded according to which principal part provides the base for each form:5

Now, let’s focus on the past tense forms:

1st person singular: (iċ) drāf ‘I drove’

2nd person singular: (þū) drife ‘you drove’

3rd person singular (hē/hēo/hit) drāf ‘he/she/it drove’

All persons plural: wē/ġē/hīe drifon ‘we/you (pl.)/they drove’6

As you can see, the ‘I’ and ‘he/she/it’ forms have a different vowel in their stem (drāf) than the ‘you’ form and the plural forms (drife/drifon). This same pattern shows up in all strong verbs, although the precise vowels used in each form differ from verb to verb.

To see what I mean, let’s look at another strong verb: brūcan ‘to use, enjoy.’7 It has the principal parts brūcan, brēac, brucon, brocen.

Focusing on the two middle ones, brēac and brucon, we can see the same pattern in the past tense of the verb, where the ‘I’ and ‘he/she/it’ forms are brēac (the second principal part) and the other forms use the vowel from brucon (the third principal part):

iċ brēac ‘I used’

þū bruce ‘you used’

hē/hēo/hit brēac ‘he/she/it used’

wē/ġē/hīe brucon ‘we/you (pl.)/they used’

This is why we need four principal parts for Old English strong verbs: you can’t predict what vowel will be used in the stem of one form based on the vowel used in the stem for another form of the same word.

But the patterns aren’t completely random. We can even tell this in modern English: there are families of strong verbs which have the same basic vowel pattern, such as drive, drove, driven; write, wrote, written; ride, rode, ridden. Or take sing, sang, sung and swim, swam, swum, and — with apologies to the Grinch — stink, stank, stunk.

The same thing was true in Old English. Strong verbs were grouped into classes according to the pattern of their vowel alternations. So verbs like drīfan ‘drive,’ rīdan ‘ride,’ and wrītan ‘write’ are all part of the same class, because they share the pattern ī-ā-i-i (as in drīfan, drāf, drifon, drifen).

Linguists have given each of these classes a number, from I to VII (typically they’re written with Roman numerals). Here’s an example of each class, with the characteristic vowel pattern highlighted:

Class I. ī-ā-i-i, e.g. drīfan ‘drive’: drīfan, drāf, drifon, drifen

Class II. ēo-ēa-u-o, e.g. frēosan ‘freeze’: frēosan, frēas, fruron, froren

Class III. i-a-u-u, e.g. singan ‘sing’: singan, sang, sungon, sungen

Class IV. e-æ-ǣ-o, e.g. beran ‘bear’: beran, bær, bǣron, boren

Class V. e-æ-ǣ-e, e.g. sprecan ‘speak’: sprecan, spræc, sprǣcon, sprecen

Class VI. a-ō-ō-a, e.g. dragan ‘draw (e.g., blood)’: dragan, drōg, drōgon, dragen

Class VII, ea-ēo-ēo-ea, e.g. healdan ‘hold’: healdan, hēold, hēoldon, healden

All of these verbs (or their descendants) still exist as strong verbs in Modern English.

But before we move on, I confess I’ve presented you with a simplified story here. Because there also exist patterns such as:

Class IIb, ū-ēa-u-o, like brūcan ‘use’: brūcan, brēac, brucon, brocen

Class IIIb, eo-ea-u-o, like weorþan ‘become’: weorþan, wearþ, wurdon, worden,

and other subpatterns and exceptions, especially in Class VII.

Part of the reason for this mess is that language is messy. But the other, more important reason is that the strong verb system didn’t originate with Old English. Old English inherited it, and, by the time it got to Old English, it had already been through about a thousand years of use.

How do we know this? Read on.

What’s Proto-Germanic for “Let it go”?

We know that the strong verb system long predates English because the closest relatives of the English language — the other Germanic languages, especially the older ones — also have almost identical systems! This tells us that the strong verb system was present in the common ancestor of all these languages, a reconstructed language we call Proto-Germanic.

Among modern Germanic languages, German still has a very robust system of strong verbs. For example, where English has drive, drove, driven, Modern German has a cognate verb — a verb descended from the same ancestral form — with the principal parts treiben, trieb, getrieben. Dutch has drijven, dreef, gedreven. Swedish has driva, drev, driven.8 Although the vowels have changed in each language, the overall pattern remains.

Let’s take a look at what the pattern looked like in Proto-Germanic. The ancestor of drive and friends was the Class I strong verb *drībaną.9 Like Old English strong verbs, Proto-Germanic strong verbs had four principal parts: the infinitive, two past tense forms, and the past participle. For *drībaną these were as follows:

Infinitive: *drībaną

Past singular: *draib

Past plural: *dribun

Past participle: *dribanaz

So we have the pattern ī-ai-i-i. What’s interesting about this pattern, as opposed to the Old English i-ā-i-i, is that you can see one thing in common among all four principal parts: the i. It’s always there, whether long or short or part of a diphthong.10 This is actually crucial for understanding the origin of strong verbs.

Let’s look at a verb from another class. I introduced Old English frēosan ‘freeze’ earlier as an example of Class II. Let’s see how its Proto-Germanic ancestor *freusaną worked:

Infinitive: *freusaną

Past singular: *fraus

Past plural: *fruzun

Past participle: *fruzanaz

Don’t worry about the alternation between *s and *z in this verb — that’s due to a very cool phenomenon called Verner’s Law, which I’ll write an entirely separate article on. Instead, focus on the vowel pattern. The Old English verb frēosan had the pattern ēo-ēa-u-o, which is a grab bag of different vowels. But when you rewind the clock to the Proto-Germanic ancestor *freusaną, you see a very clear pattern involving the vowel u: eu-au-u-u.

Ok, now it’s getting exciting (well, for nerds). Let’s look at Class III. Our example verb for Class III in Old English was singan ‘sing.’ This had the pattern i-a-u-u. Let’s look at the principal parts of its ancestor, *singwaną ‘sing’:

Infinitive: *singwaną

Past singular: *sangw

Past plural: *sungun

Past participle: *sunganaz

Here, we say the same vowel pattern as in Old English: i-a-u-u. Still nothing in common… unless we think outside of the box a bit.

What if we think of the pattern as encompassing also the consonant after the vowel? So instead of i-a-u-u, the pattern becomes in-an-un-un, and we get the commonality in Class III that we had in the first two classes. It’s just that, in Class III, the common element isn’t a vowel but a consonant.

So we have these patterns for Classes I–III:

Class I: ī-ai-i-i (i is the common element)

Class II: eu-au-u-u (u is the common element)

Class III: in-an-un-un (n is the common element)

Now, this isn’t the whole story of Germanic strong verbs. Classes IV–VII introduce some wrinkles we won’t have time to discuss in this article. But you can clearly see the overall principle behind strong verbs in action, or at least half of the principle.

That is, we understand the thing that the various forms of the strong verb have in common: either a vowel i/u, or a consonant n, depending on the class. But we don’t yet understand the other part, the part that changes from one principal part to another. So far it seems random.

And, to top it off, we don’t understand why these principal parts exist in the first place.

To learn all that, we need to go back even further than Proto-Germanic, all the way to Proto-Indo-European.