Why people feel entitled to correct your grammar online

A natural history of the language police

“Just a nitpick, but…”

Anyone who writes online has run into commenters like this: people who are more interested in critiquing the way that an author used a word, phrase, punctuation mark, or stray bit of verb conjugation than engaging substantively with the author’s ideas.

Whether you call them nitpickers, pedants, or, more kindly, language mavens, this type makes a frequent appearance in comment sections all over the internet.

While I doubt many writers enjoy receiving these comments, I’m not here to condemn the people who leave them. If that were my goal, I would have named this essay “Linguist DESTROYS grammar nitpickers with facts and logic.”

No, I do not wish to criticize this practice. What I want to do is explain it and place it in its historical context. Once I’ve done that, you can decide for yourself how to judge the language police the next time you meet them in the comments section.

In other words, we’re interested in the question: Why would someone take time out of their day to correct the writing of a stranger?

To find the answer, we’ll need to travel back in time to the Middle Ages.

You’re reading The Dead Language Society. I’m Colin Gorrie, linguist, ancient language teacher, and your guide through the history of the English language and its relatives.

Subscribe for a free issue every Wednesday, or upgrade to support my mission of bringing historical linguistics out of the ivory tower and receive two extra Saturday deep-dives per month.

If you upgrade, you’ll be able to join our ongoing Beowulf Book Club. You can also catch up by watching our discussion of the first 1962 lines. Our next meeting is Thursday, December 4.

500 ways to spell ‘through’

The idea of a single correct way to use language is born very late in the history of English.

We can see this most clearly in how words have been spelled throughout history. It is not technically grammar, but then again, many of the “corrections” we see online do not involve grammar in the sense that most linguists use the term, that is, referring to the rules for combining words, phrases, and parts of words to express meaning.

But let’s speak a bit more loosely today: we can consider the preoccupation of nitpickers to be “grammar,” just as many of these nitpickers describe themselves as “grammar Nazis.”1

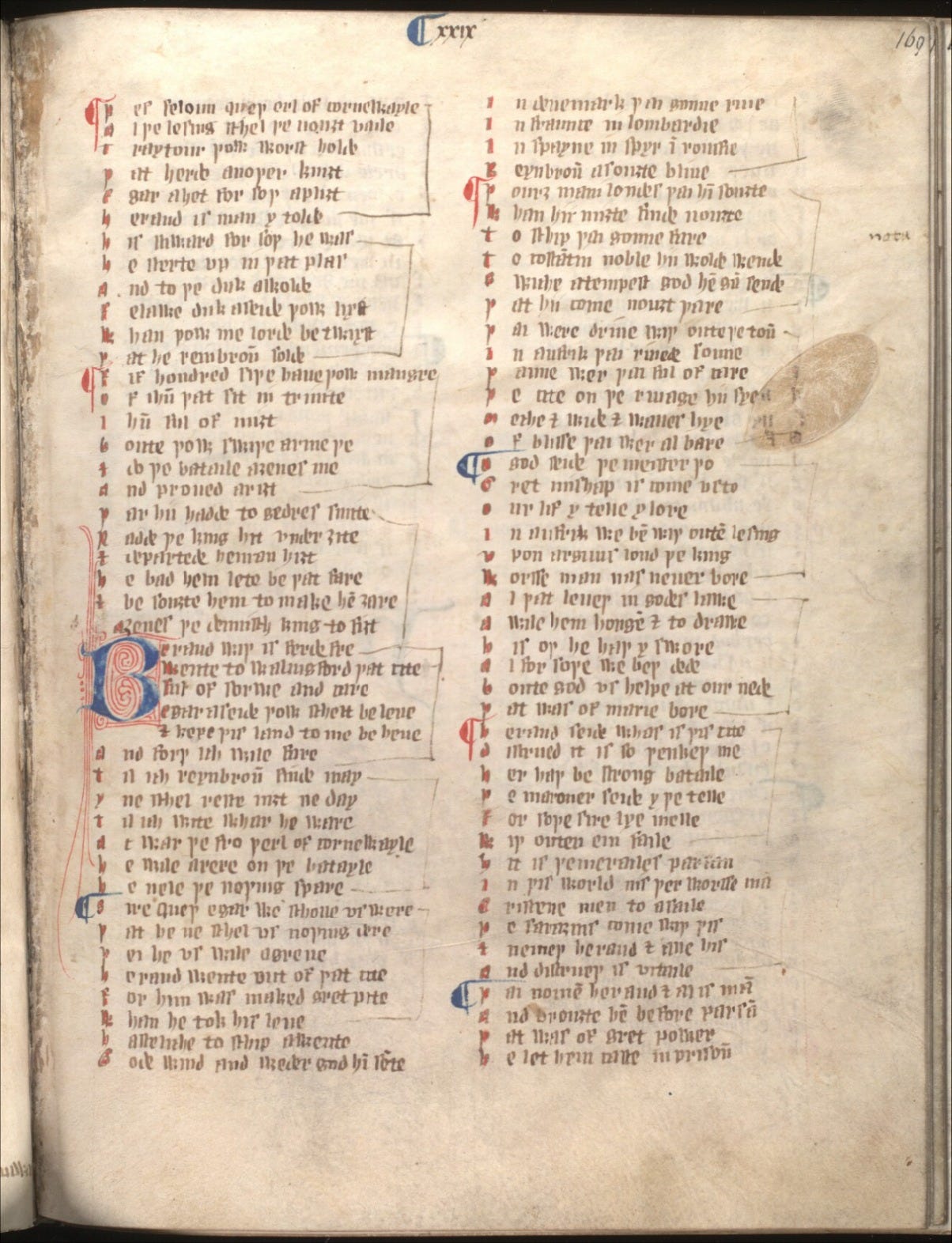

Whatever we call them, we need to keep nitpickers away from medieval texts for their own good. They’d have a fit. In fact, even the most broadminded of modern readers experience culture shock when learning to read medieval texts, where it’s not uncommon to see the same word spelled in many different ways by the same scribe, even on the same page.

This variation occurred because there was simply no notion at that time that a particular word had a single spelling. This laissez faire spirit was taken to an extreme in the later Middle Ages (1100–1500), where a single word such as through could be spelled in 500 different ways (thurght, drowgȝ, yhurght, þorowe)2 over the period.

The reason for this spelling anarchy is that the late Middle Ages were precisely the age when English was not a prestigious language: that role was played by French and Latin. As a result, there wasn’t much pressure for writers to conform to a standard.

Instead, writers simply wrote words how they felt like writing them, which meant that the many different ways you could conceivably write a word (reflecting everything from different regional dialects to scribes’ personal preferences) made it onto parchment.

But even outside of this chaotic four hundred years, in eras where English had more prestige, there was still a good deal of variation in how words were spelled up to around 1700.

For example, English writing had some prestige in both the Old English period (roughly 700–1100) and the Early Modern Period (1500–1700), and when you read texts from these periods, you still see some variation in how words were written, even in relatively formal contexts.

If it seems strange to you that someone might spell a word in two different ways in close succession without an apparent reason for doing so, consider that you probably do the same thing, just in limited contexts.

Look over some of your recent text messages and see how often you spelled and using those three letters, and how often you used symbols like & and +. Or consider how there are multiple valid spellings of numbers: alongside three we have 3 and III.

There are sometimes reasons why we choose one variant or another: for example, our convention is to write phone numbers using numerals (527-1111) rather than the spelled form of the numbers (five two seven, eleven eleven).3 But, often enough, there is no identifiable reason. You just write “&” without thinking too much about it.

And so it was in centuries past for every word.

But the spelling of English gradually began to settle into a single standard form, a process which began around 1350 and lasted roughly until 1700. Nevertheless, even to day there is still a certain amount of debate about how to spell certain words, such as colour (vs color) and harmonize (vs harmonise).4

Spelling, however, is not the principal target of nitpickers today. But just as spelling became considered something you could do correctly or incorrectly, so too did other aspects of language, including pronunciation, word usage, and grammar proper.

English is so inconveniently alive

Anyone who interacts with people from different parts of the English-speaking world will have remarked on how language changes from place to place.

What I call pop you might call soda. And anyone who has watched two or more generations grow up and take their place in the world will surely have remarked on how language changes over time, as what was once groovy became tubular, and what was once sick became dope.

This kind of diversity and change has always been a feature of any living language. But there is also an opposing force: a drive towards uniformity. This too, has probably always been there. Given that human beings use language as a way of marking that we belong, we’ll always have some pressure to use language like those around us.

But the modern world has given birth to a new kind of drive towards uniformity: the ability of a single standard form of a language to be promulgated widely. Before the ability to mass-produce texts afforded by the printing press, writing had to be done by hand. And anything done by hand has the potential for variation, as we saw with spelling in the Middle Ages.

But when texts could be copied exactly, as only a machine can do, a single variety of the language could spread throughout the entire community of speakers of that language. It was in 1476 that the first printing press arrived in England. The physical technology was now in place for linguistic uniformity to gain the upper hand over diversity.

But a key piece of social technology was needed: the idea that the English language should in fact be fixed. It is no accident that the printing press came to England at roughly the outset of the English Renaissance (approx. 1500–1650), a great rebirth of interest in the culture and, especially, the languages of the Greek and Roman world.

The dead languages.

One thing that’s interesting about dead languages: they don’t change. Unlike living languages, dead languages have fixed systems of spelling and grammar.

The writers of the Renaissance valued Latin and Ancient Greek so highly that they wanted to remake English in its image. But they found English in too wobbly a state to attain the heights of the classical languages. English needed fixing, both in the sense of pinning the language down and in the sense of repairing any decay the language might be subject to.5

A cottage industry therefore grew up in the 17th and 18th centuries with the aim of fixing the English language, in other words, making it more like a dead language.

This industry employed a bevy of professionals (and amateurs) dedicated to the craft: including grammarians, lexicographers (dictionary writers), and orthoepists (people who taught “correct” pronunciation).

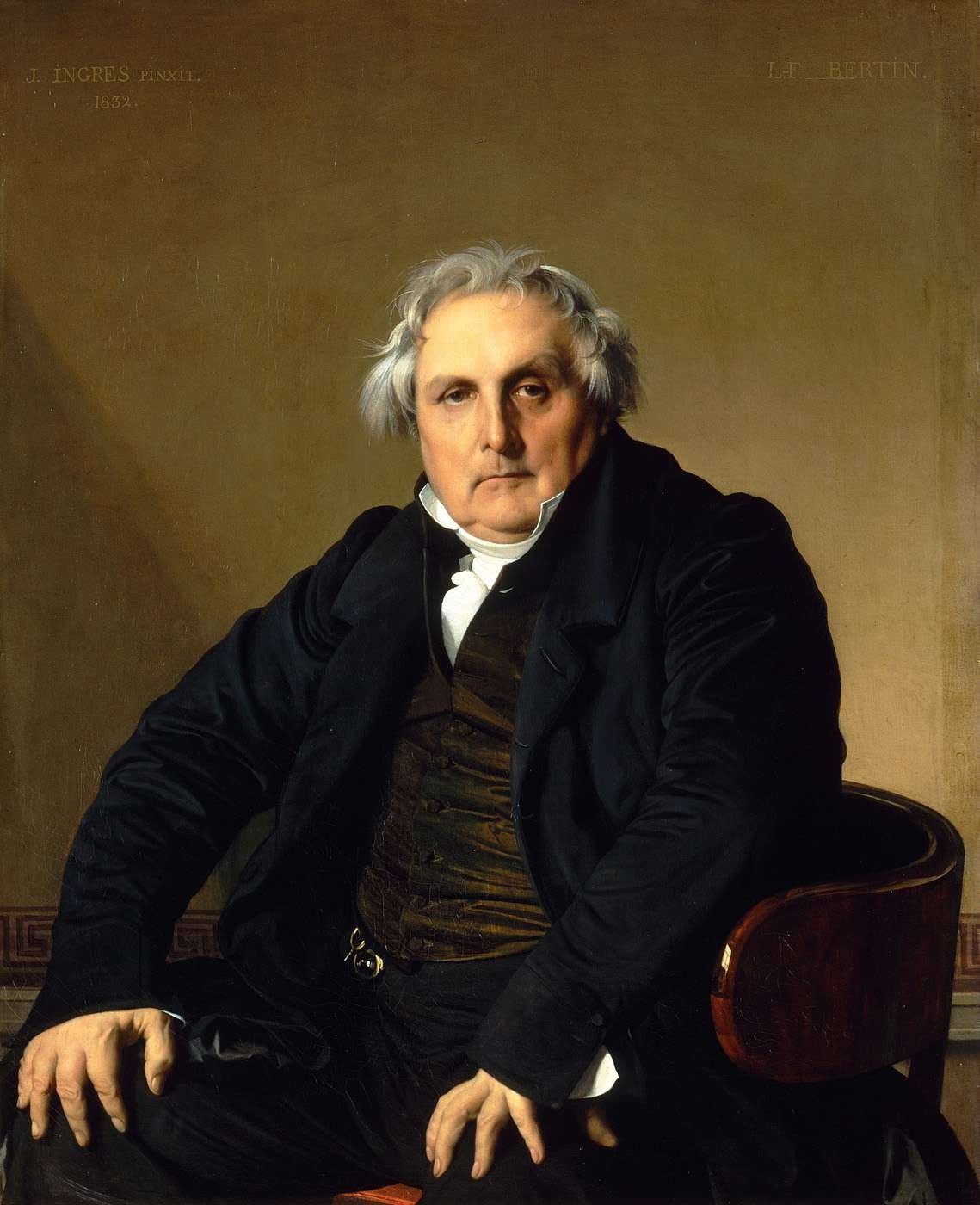

The 18th century also coincided with the rise of the middle class, who, as an upwardly mobile group, had a tremendous amount of anxiety over their place in the social hierarchy. Language became an arena where this anxiety could be assuaged somewhat, by the judicious use of “correct” language. Even if your education had not been all that might have been hoped for, you could at least sound like you’d been well brought up if you spoke and wrote “properly.”

So there was always a market assured — and there still is! — for any grammarian with a book promising to tell you how to sound respectable. But you’d always have to be on guard against any gaffes that might reveal that you’re not quite as respectable as you make yourself out to be.

This 18th-century milieu is the source of much of our contemporary thinking about grammar, at least outside of linguistics departments. It’s where the focus on grammatical “error” comes from, and it marks the date of birth of an all-too-familiar character.

Read this 1762 letter and tell me if you recognize the sentiment:

Pray have you seen Dr Louths English Grammar which is just come out? It is talk’d of much. Some of the ingenious men with whom this University overflows, are picking faults and finding Errors in it at present. Pray what do you think of it? (Letter from Thomas Fitzmaurice to Adam Smith)

Lo, the grammar nitpicker is born.

So much for the historical context of the grammar nitpicker. We have seen now why the idea of a correct way to use language emerged, but we’re still missing a part of the story: Why do ordinary people take time out of their day to tell strangers on the internet that they’ve violated some rule of respectable language use?

I’m doing this for your own good

In a classic 1995 book,6 linguist Deborah Cameron introduced the concept of verbal hygiene, first defined roughly as “the urge to meddle in matters of language” (xix) and the practices that grow out of this urge.

One of these practices is the familiar phenomenon of people who write letters to newspapers — remember, this came out in 1995 — complaining about this or that misuse of language, found either in the paper itself or in society more broadly.

Here we can see the immediate ancestor of our contemporary nitpicker, who, following the wider shift in media consumption from print to digital formats, has now found a comfortable home in the comment section of blogs and social media platforms across the internet.

What is the inner world of such a person like?

Their behaviour can be explained by the fact that they believe that how we use language matters.

In this way, they’re not so different from you and me. Forgive me if I make an assumption about your interests, but if you’re spending your spare time reading articles like these, you must care about language in some way.

But care for language comes in many forms. When we look at the attitude of linguists, those who have gone pro with their care for language, most have the firm belief that we should be descriptive in how we approach language rather than prescriptive. Linguists generally prefer to take language as a part of nature, that is, something which can be described, but which should really be left alone to develop of its own accord.

A core part of any introductory linguistics course involves stressing this distinction: linguistics is not about prescribing what should be done with language, but with describing language as it actually is. But try submitting a paper full of “spelling mistakes” — or, rather, alternative orthographic choices — to a linguistics journal and see how far that descriptive attitude actually extends.

(I won’t dwell on the irony of introductory linguistics courses prescribing a descriptive attitude towards language, because I think it’s largely for the best that they do this.)

The fact is that “meddling in matters of language” is something that everyone does, even when we only meddle in our own language. If you’ve ever edited a text message to change how it reads, you too have meddled.

Meddling arises from the human ability to reflect on our use of language. In fact, this reflexive ability seems to be a core part of human language: it’s the thing that allows us to request clarification when we realize we don’t understand something, to express ourselves clearly when we need to, or to try to obscure our real intentions behind euphemisms when we’re afraid of how our words might be taken. It’s the thing that lets us use language in a playful way, to recognize when others are doing so, and to understand what it means when someone has told us a joke.

And yet, even if the urge to meddle is human, there is still a difference between editing one’s own text messages so they don’t come across as brusque and writing to strangers with criticisms of how they use language.

There are two differences between the nitpicker and the rest of us. One is that, while everyone has ideas about how language should be used, the grammar nitpicker has thoroughly internalized the 18th-century idea that there is one proper way of using English. And you can learn about that proper way from a book which will save you from any embarrassing mistakes.

Another variation on the theme is that the proper way of using English was finally discovered in the year the commenter turned 15. All innovations prior to that point are natural and laudable, while all innovations in the years that followed are sure evidence of the decay of civilization.

Wherever the nitpicker’s standard comes from, there is still one more difference between the nitpicker and the average person, which is that the grammar nitpicker is an altruist. A humanitarian. The nitpicker just wants the best for you, which is that you should stop embarrassing yourself further.

Also, you should set a better example for your readers! You, a writer, should know better than to end a sentence with a preposition.

This is the sort of nonsense up with which the nitpicker cannot put.7 Imagine if an impressionable young writer should read your mistake and take it as something to be emulated. Won’t somebody please think of the children?

This is the impulse that compels the nitpicker to click “comment.”

Their heart — if they’ll permit me the use of they to refer to a non-specific singular antecedent such as the nitpicker8 — is in the right place.

Ultimately, altruistic impulses are hardly something that I’d want to condemn. Nor can I tell you that you should be descriptive about language rather than prescriptive. No human being is consistently descriptive about language, anyway. We all prescribe, even if we only prescribe to ourselves.

All that I would hope to impart to any nitpickers reading this is that they’ve imbibed a particular idea about how language should be used. This idea is rooted in a historical anxiety about social status that the nitpicker may not even share, especially if the nitpicker is of a particularly democratic or egalitarian bent.

What’s more, the writers they are addressing may not share this anxiety either. Most writers have anxiety enough without having to worry about whether they’d be found out as a fraud in 18th-century London.

A nitpicker may be addressing a writer with a more “medieval” approach to writing: when each essay is handcrafted, you should expect some natural variability in the results. Think of it as artisanal writing.

Speaking for myself, if you understand what I’m saying in my articles, and perhaps even find it a pleasant experience to read them, then I feel I’ve done my duty as a writer, even if I’ve dared to cheekily split an infinitive here or there.

In the end, the nitpickers will always be with us. But now that you understand where they came from and why they do what they do, you can judge for yourself whether they are a force for good or evil in the comments section.

A name no one would self-apply where I come from.

If this number means anything to you, we must have been neighbours at some point.

These debates are often vehicles for nationalistic sentiments, as different countries have adopted slightly different spelling standards. The particular combination of -ize and -our spellings used in this Substack, for example, is characteristic of Canada.

Similar, and, in fact, more extreme, developments were happening in other European countries at the time, including the establishment of language academies, such as the Académie française (1635), which put the weight of the state behind the standardization of the French language. If Jonathan Swift had gotten his way, English would have had an academy too.

Cameron, Deborah (1995[2012]). Verbal Hygiene. 2e.

A variation of this phrase is often attributed to Churchill, probably apocryphally.

They won’t.

Sorry to nitpick, but I think you meant to say: “even if I’ve dared to cheekily an infinitive here or there split.”

I *may* have put a piece of spinach in my teeth on purpose. People have had spinach in their teeth for centuries, after all. However I probably did not and appreciate when people tell me it is there so that I don't spend the whole evening with people trying to talk to me but actually the whole time they are thinking "should I tell her? No, she might not want to be corrected"