How rhyme works (and why)

A lesson in the anatomy of the syllable

Some of the first snippets of language that we hear as babies — at least those of us who grew up in the English-speaking world — consisted of rhymes. Why did Jack and Jill go up a hill specifically, rather than a mountain? Could Little Miss Muffet have sat on anything but a tuffet? What is a tuffet anyway?1

Rhyme makes things catchy and easy to remember. That’s why nursery rhymes are so central to how we communicate with the very young. Whether it’s from experiences like (endlessly) hearing these nursery rhymes in our most formative years or not, rhyme is part and parcel of a child’s developing knowledge of the English language.

Growing up, an English speaker acquires an almost instinctive fluency and comfort with rhyme. As a result, it’s not hard to come up with rhymes, even on the fly. But it’s not so easy to define what rhyme is, and what exactly it means for two words to rhyme.2

You’re reading The Dead Language Society. I’m Colin Gorrie, linguist, ancient language teacher, and your guide through the history of the English language and its relatives.

Subscribe for a free issue every Wednesday, or upgrade to support my mission of bringing historical linguistics out of the ivory tower and receive two extra Saturday deep-dives per month.

If you upgrade, you’ll also be able to join our ongoing Beowulf Book Club, which meets again on October 9. You can also catch up by watching our discussion of the first 1395 lines (part 1, part 2, part 3) right away.

Let’s start with the simplest cases: words of a single syllable.

To begin with, we can all agree that dog rhymes with fog. [edit: apparently for some Americans, these are separate!? If that’s the case for you, feel free to substitute a different word here, I cannot for the life of me figure out which of these words rhyme for you.]

These two words rhyme because they share something: specifically, they share the latter part of the word, in this case, -og. If simply sharing the latter part of a word is enough to create a rhyme, this means that other words ending in -og should rhyme with fog too: for example, log, bog, cog, and so on.

So far, so good.

Now let’s confront another fact: bag doesn’t rhyme with fog, even though they share a final consonant -g. Neither does song rhyme with fog, even though they share a vowel -o-.3

This suggests that, in order for two words to rhyme, they have to share both the vowel sound and the final consonant.

Let’s expand our dataset. String rhymes with bring. But both also rhyme with king. From this, we learn that the consonant -r-, the one that comes before the word’s vowel, isn’t needed to form a rhyme.

It seems, therefore, that our words of one syllable can be broken down into two parts: (1) the part of the syllable relevant for rhyming, that is, the vowel and the consonant that comes after it; and (2) the part irrelevant for rhyming, that is, everything that comes before the vowel.

Let’s give these two parts names: the part relevant to rhyme we’ll call the rime. You can spell this rhyme if you want, but it’s nice to be able to distinguish rhyme (the relationship between two syllables) from rime (the part of the syllable). The part of the syllable irrelevant to rhyme we’ll call the onset.

Two syllables are said to rhyme if they share a rime. Got it? Not at all confused? Excellent.

Rather sneakily, I switched from talking about what makes words rhyme to what makes syllables rhyme. You’re not going to let me get away with that, are you?

We have rules for that kind of thing

Let’s now expand our ambitions to encompass words of more than one syllable.

For example, what does attack rhyme with? Back, lack, Jack, track, and anything else that ends in that sequence of sounds spelled -ack (even if those sounds are spelled differently, such as plaque). For the purposes of rhyme, attack acts just like the words of one syllable we analysed earlier. We can ignore its first syllable, and just treat it as if it were the word tack, which rhymes with any word that shares the rime -ack.4

We can ignore the first syllable of attack because attack has its stress, or accent, on its last syllable: if we mark the stressed syllable with an acute accent (´), we’d write it like attáck.

To see why this matters, let’s compare attáck with another, very similar two-syllable word: áttic, which, unlike attáck, has its stress on its first syllable. As it turns out, we’re not entitled to ignore the first syllable of áttic. Áttic rhymes with words like státic, that is, with words with (a) matching rimes in their stressed syllables, and (b) fully matching final syllables.

Note, however, that áttic does not rhyme with tick, thick, or Rick, that is, with monosyllabic words whose rimes match only the rime of áttic’s final syllable, -ic/-ick.5

Traditional poetic terminology gives us language to describe the difference between rhymes like attáck vs back, on the one hand, and áttic vs státic, on the other. Rhymes like attáck vs back, where we only need to match the rimes of single syllables, are called masculine rhymes. Rhymes like áttic vs státic, where you need to consider two syllables in the rhyme, are called feminine rhymes.

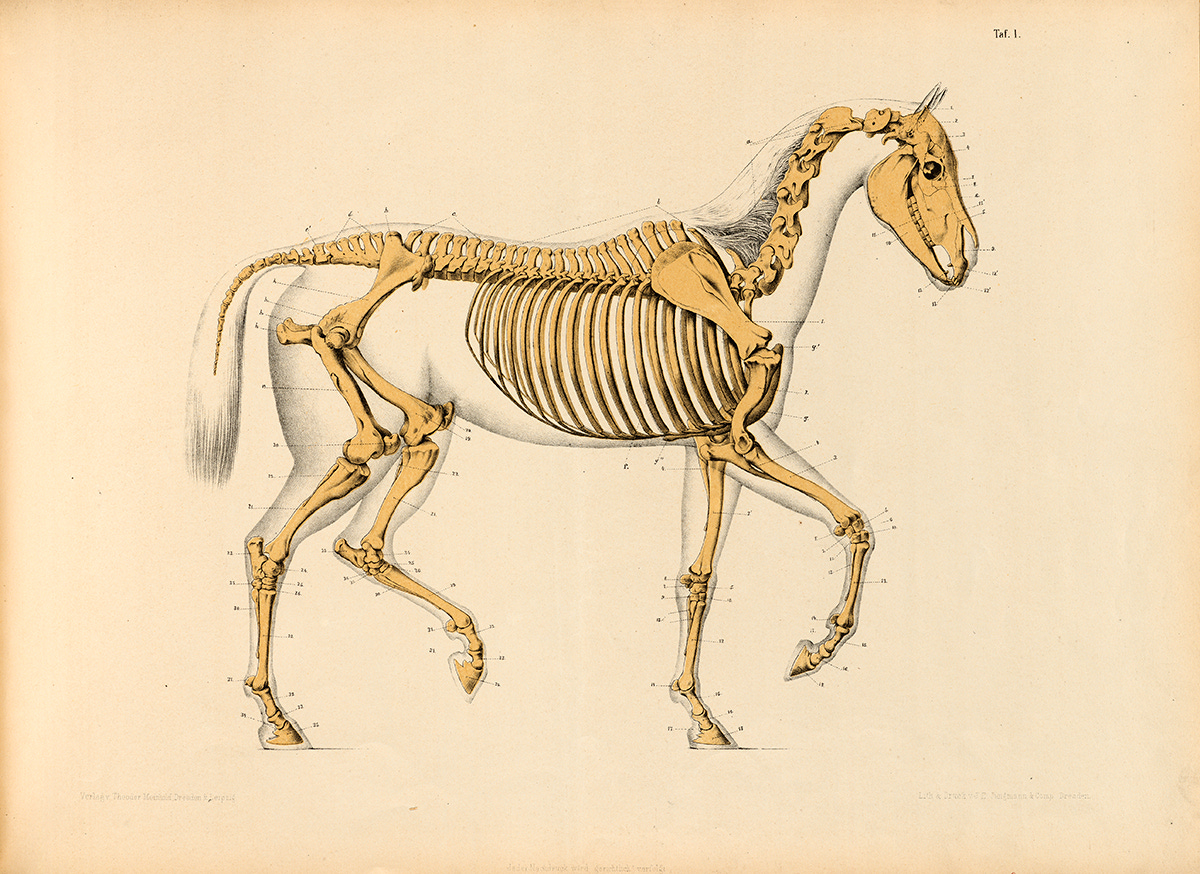

The reason for this strange masculine vs feminine terminology originates in French poetry, where feminine nouns and adjectives (like une grande chose ‘a big thing’ — I’m using bold here to indicate stress, since the acute accent is actually used in French) tended to end in the letter -e, which was pronounced (then) as an unstressed vowel.6 Masculine nouns and adjectives, on the other hand, (like un beau cheval ‘a beautiful horse’) tended to end in a stressed syllable.

So we can make a more general rule, which we’ll call the Rhyming Rule.

The Rhyming Rule: Words rhyme when (a) the rimes of their stressed syllables are identical, and (b) all syllables following the stressed syllable are identical.

Now let’s test our Rhyming Rule on words of three syllables: what does grávity rhyme with? By my reckoning, grávity, which has its stress two syllables away from the end of the word, rhymes only with cávity, concávity, and deprávity, that is, with words which follow our rhyming rule.

These rhymes, which require one rhyme and two full syllables to match, are called dactylic rhymes, since the stress pattern of words like grávity, that is, stressed-unstressed-unstressed, is called a dactyl in traditional discussions of poetry.

It’s pretty hard to make dactylic rhymes work, so it’s always impressive when a poet pulls it off.

But wait, what about what Eminem does with the word grávity in “Lose Yourself”?

Snap back to reálity, ope, there goes grávity

That doesn’t quite match the Rhyming Rule, but it works. Why?

I’m not going to defend “Mom’s spaghetti”

To understand why Eminem’s dactylic rhyme works, we need to consider that our Rhyming Rule describes only one particular kind of rhyme, that is, perfect rhyme. There are other kinds of rhyme, whose rules are formulated differently. So let’s rename our Rhyming Rule to the Perfect Rhyming Rule:

The Perfect Rhyming Rule: Words rhyme perfectly when (a) the rimes of their stressed syllables are identical, and (b) all syllables following the stressed syllable are identical.

The relationship between reálity and grávity is one of imperfect rhyme,7 which is a loosened version of the Perfect Rhyming Rule. But to formulate an Imperfect Rhyming Rule, we’ll need a little bit more help from linguistics.

As we saw before, the Perfect Rhyming rule requires us to be able to make reference to syllables and to distinguish two parts of syllables: onsets and rimes.

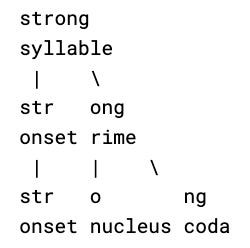

Let’s take a syllable like strong as an example: this rhymes with gong and long, so we know the rime is -ong. This means the onset must be str-.

But, as it turns out, we can break down the rime further into two separate components, the nucleus, which consists of the vowel, and the coda, which consists of the consonants after the vowel.

Here’s a diagram of how strong breaks down into its component parts:

Imperfect rhyme, then, is a situation where two syllables don’t match the rime fully. Usually, either the nucleus or the coda matches, but not both (as that would be perfect rhyme). Imperfect rhyme is frequently used in hip hop as it allows for more multisyllabic rhymes, feminine, dactylic, and beyond.

Let’s look at some examples of imperfect rhyme:

attáck has perfect rhymes lack and back, and imperfect rhymes glad and pat (matching nucleus) and walk, puck (matching coda)

áttic has the perfect rhyme státic, and imperfect rhymes pánic and tráffic (matching nucleus + final syllable) and antibiótic (matching coda + final syllable).8

grávity has perfect rhymes cávity and deprávity, and imperfect rhymes reálity and insánity (matching nucleus + final syllables) and proclívity (matching coda + final syllable).

So we can formulate an Imperfect Rhyming Rule like this:

The Imperfect Rhyming Rule: Words rhyme imperfectly when (a) either the nucleus or coda of their stressed syllables are identical, and (b) all syllables following the stressed syllable are (almost) identical.

Although rhyme, be it perfect or imperfect, is used for artistic effect, it’s built using categories that are linguistic in nature: syllable, nucleus, coda, and rime. And, as it turns out, these categories are of the highest importance for purely grammatical phenomena in a wide range of languages.

Let’s take an example from Latin. While the position of the stress in an English word is arbitrary, that is, you just have to know it, the position of the stress in a Latin word9 is entirely determined using a rule. It’s a pretty intricate rule, but it uses these same linguistic categories that we used to define rhyme: syllable, coda, and nucleus.

Since Latin isn’t our topic today, don’t worry about the details. Just look at the rule in a nutshell (I’ve placed some things in boldface to draw your attention):

In a word of two syllables, the stress goes on the second-last syllable, e.g.:

á-ger ‘field,’

vā́l-lum ‘rampart.’

In a word of three or more syllables, the stress goes on the second-last syllable if that syllable has a coda or a long nucleus, e.g.:

vi-dḗ-re ‘to see’ (long nucleus ē in dē),

pu-él-la ‘girl’ (coda l in el).

Otherwise, the stress goes on the third-last syllable, e.g.:

fḗ-mi-na ‘woman’ (no coda, no long nucleus in ni),

ḗ-li-git ‘he/she/it chooses’ (no coda, no long nucleus in li).

The specifics of the Latin rules don’t matter to us today. What does matter is this: When the grammar of Latin needs to count something to determine where stress goes, it looks at the same entities English-speaking poets and rappers look at — syllables, nuclei, and codas.

Or, closer to home, look at English words like helter-skelter, easy-peasy, hoity-toity, eensy-weensy, and so on. These words owe their very existence to the rules of rhyme.

So, although rhyme is characteristic of poetic use of the English language, it’s doing nothing more than what poetic use of language does the world over: pressing the ordinary categories of language into service and using them for artistic effect.

Old English alliterative verse cared about matching initial consonants of stressed syllables. Medieval Chinese 近體詩 jìntǐshī poetry cared about alternating sequences of tones. Ancient Greek and Latin poetry fussed over sequences of long and short vowels, and whether or not syllables had codas.

But in each of these poetic traditions, the raw material the poetry works with is nothing but the basic categories offered by the language itself. And that’s why a knowledge of rhyme comes along with a knowledge of English. Being able to rhyme is a direct application of the knowledge English speakers instinctively use to form syllables and whole words.

And if you don’t believe me, ask Humpty Dumpty. Just keep him away from walls.

Apparently, some sort of mound.

We’ll be primarily considering perfect rhyme, that is, the kind of rhyme that exists between top and pop, sunny and funny, and gravity and depravity. There are, however, other, looser kinds of rhyme, which we’ll get to before the end of the article.

Although there might be something else going on between the two words log and song. We’ll come back to this later.

IPA [æk].

You could debate whether the i vowel in tick matches the i vowel in attic exactly. But even if the vowels did match exactly, the two words would not rhyme, at least not in the sense of perfect rhyme.

In most varieties of French, this -e vowel tends not to be pronounced today.

Also known as half-rhyme, near-rhyme, sprung rhyme, slant rhyme, and, less flatteringly, lazy rhyme and bastard rhyme.

In case you’re wondering why I analysed the t in antibiotic as matching the coda of the t in attic, single consonants after stressed short/lax vowels, like the t after the a in attic, are often analysed as ambisyllabic, functioning both as coda of the syllable at- and onset of the syllable -tic. Let me know if you’d like an article about this phenomenon, as it’s both intricate and interesting.

Since we have lots of Latin words in English, a good chunk of our vocabulary works this way too.

I suspect you will hear this from others, but dog doesn’t rhyme with fog in my accent.

For 50+ years I’ve been fascinated by Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” with its mishmash of interior rhymes. One in particular “..get sick, get well, hang around the inkwell….” rhymes the same word “well” with itself but in two distinct meanings - cured and reservoir. The entire lyrics of the song, sung at its ripping tempo almost becomes a tongue twister.

Once again I’m reminded of an observation that poetry/lyrics are processed and even stored in a separate part of our brains than prose. My relative who suffered catastrophic brain damage and barely able to construct two word sentences was fully capable of reciting nursery rhymes, Christmas carols etc. learned in childhood long before her Injury.