Why English doesn’t use accents

And why French is full of them

Canterbury, AD 1105

The cold of the stone floor in the scriptorium creeps up through Godwin’s boots. He pays it no mind. Before him lies a copy of the Chronicle, just arrived from the old capital of Winchester. In it is written the history of the English people. His people.

Today, his job is to make another copy. No difficult task for Godwin, or any monk.

But Abbot Robert will want to inspect the work before vespers. Abbot Robert. A Norman. Last week, the abbot pointed at Godwin’s lettering and called it “crude.” The word still stings.

Godwin’s quill forms the letters scip. The passage is about a foul fleet of ships: the raiding parties of Danes that had harried the coast, whom the great King Alfred eventually brought to heel. If only England had a king like that today.

Godwin stares at the word. Scip. It’s the right word, the right spelling. The ‘sc’ makes the same sound that the Normans spell ‘sh.’ But Robert won’t see it that way. For him, this will be nothing but Saxon stubbornness.

Godwin takes up his knife. The steel edge scrapes away the ink, taking a thin layer of the vellum with it. He smooths the spot and writes the word again, this time as he knows Robert will want it: ship. An English word, somehow made foreign.

He works on, his hand steady. He reaches a later entry: the arrival of a new queen. Pride or the devil takes hold of his soul, and he writes cwen. He thinks with a smile of Edith, the last English queen, a woman of his grandfather's time.

Then the smile vanishes. There are no more English queens or kings. Only Normans.

He scrapes the vellum clean again and writes it like a Norman would: queen. He writes the ‘e’ twice so the Normans know to drag out the sound. The ink settles, black and final.

He looks at the two words. Ship. Queen. This is writing that even a Norman abbot will find acceptable. Good work, he’ll surely say. But Godwin isn’t so sure. He dips his quill again into the ink and continues to rewrite the past.

You're reading The Dead Language Society. I'm Colin Gorrie, linguist, ancient language teacher, and your guide through the history of the English language and its relatives.

Subscribe for a free issue every Wednesday, or upgrade to support my mission of bringing historical linguistics out of the ivory tower and receive two extra Saturday deep-dives per month. You can also join our upcoming summer Beowulf book club, which starts in just a few short weeks!

This weekend we’ll be exploring the history of colour words: how ‘blue’ is more recent than you think, why ‘black’ and ‘bleach’ come from the same root, and how global trade gave us our modern-day rainbow.

Blaming the French (again)

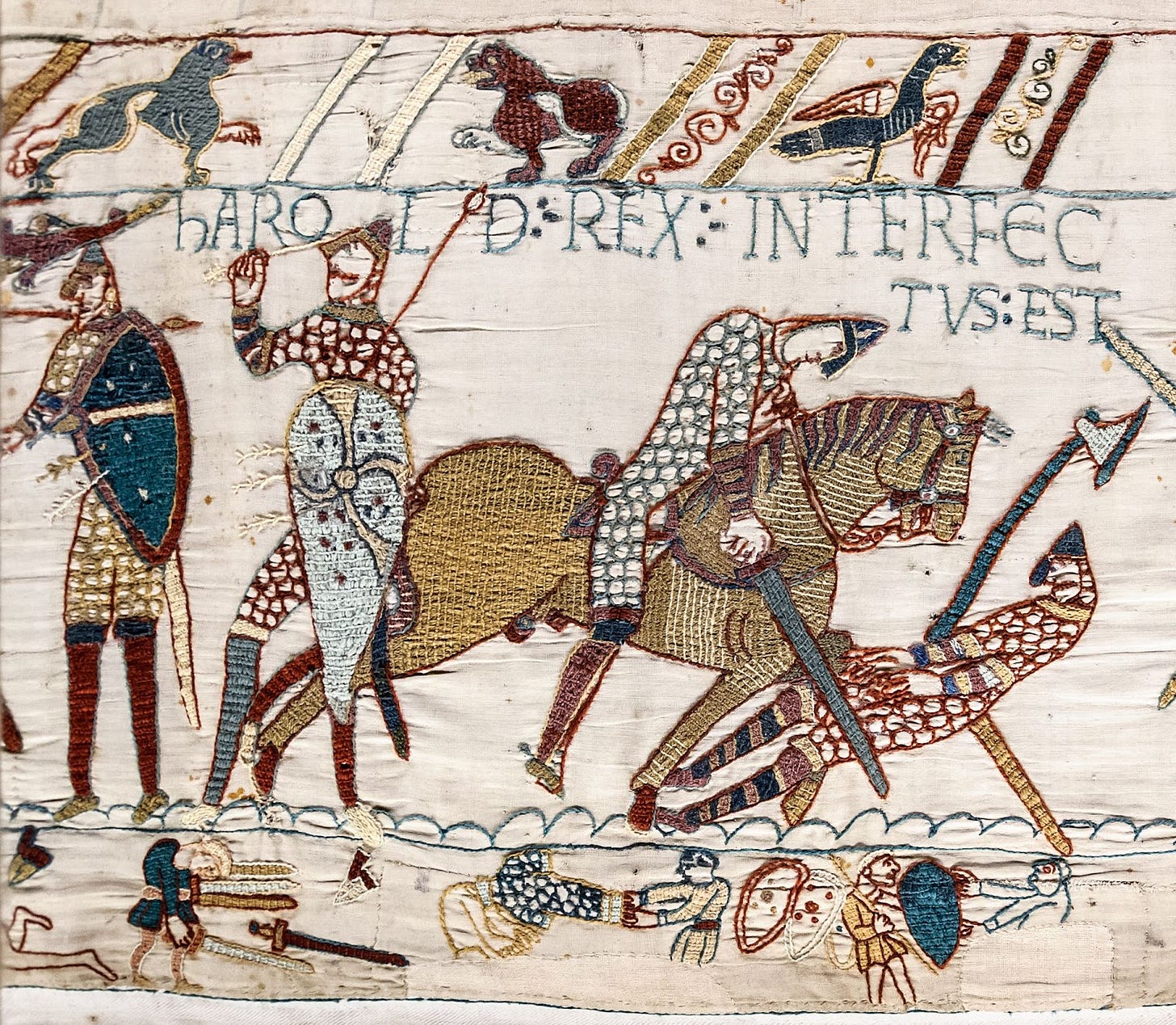

Our fictional monk Godwin lived in the wake of the single most significant event in the history of the English language: the Norman Conquest of 1066.

Before the Conquest, English — albeit an old form of English — was the language of power and government in England. After the Conquest, French took its place for centuries.

It was but a temporary replacement: English eventually re-established itself in the halls of power, thanks to the gradual loss of English territory in France and the birth of a new English identity during the Renaissance. But the period of French dominance left its mark on all aspects of the language, from vocabulary to pronunciation. And, as Godwin found to his chagrin, it had a revolutionary impact on English spelling.

In fact, this early French influence over English, which arose from the Norman Conquest, is the beginning of the reason why English is written without accent marks (é, à, ç, etc.), or, as linguists call them, diacritics, today.

Let’s keep calling them diacritics, since accent can mean so many things, from different regional ways of speaking to where in a word you place the emphasis.

It may surprise you to read that English is written without diacritics due to French influence. After all, French is written with plenty of diacritics: écouter ‘listen’, à ‘to’, château ‘castle’, Noël ‘Christmas’, Français ‘French’.

But the French that the Normans brought to England was not French as it’s spoken and written today: it was a different, older form of the language — and one written very differently from the French you would find in a livre today.

One big difference between the French of 1066 and the French of 2025 is in the use of diacritics. Diacritics only became a part of standard French writing much, much later than the time of the Norman Conquest. So the French brought over by the Normans was written without them. And when these scribes took up the task of writing English, they carried over their French habits of writing.

Why are diacritics used?

These scribal habits did include the use of diacritics, but only for the purposes of abbreviating certain common combinations.

After all, parchment is expensive, and you don’t want to waste any space. But crucially, scribes did not use diacritics for the main reason we use them today: to show that a letter is not pronounced how you would otherwise expect it to sound. For example, the cedilla (¸) is written under a c in French to show that that c is pronounced as an ‘s’ rather than a ‘k’, as in Français ‘French’ or leçon ‘lesson’.1

The use of diacritics arises out of a mismatch between an alphabet and the language it’s being used to write: if an alphabet were well adapted to a language, it would have letters for all the language’s sounds. But this is rarely the case: alphabets are usually chosen for historical and cultural reasons. For example, English is written in the Latin alphabet because England was converted to Christianity by the Roman church. French is written in the Latin alphabet because the language itself descends from Latin, after having undergone many changes.

In both French and English, the Latin alphabet’s limited set of letters was insufficient to write all of the sounds needed in the language. For example, Latin had no th sound, as in faith. But Old French did have such a sound: since it was made in the same region of the mouth as the t sound (with the tip of the tongue), French scribes used the combination th to write it. The t told you what basic kind of sound it was, and the h told you that it was a different sound than the one you expected. So for these French scribes, adding another letter solved exactly the same problem that later French spelling used diacritics for.

This was the French habit that the Normans brought to England: the use of extra letters to spell sounds that the alphabet didn’t have special letters for. This is why English has combinations like sh, th, ee, oo, ou that each make only a single sound.2

Writing in the Renaissance spirit

The writing practices we have been talking about developed during a time when all writing was done by hand, by a relatively small group of people, dispersed over a wide area. This small group of scribes was, in turn, writing for a relatively small audience: literacy was not widespread in Europe during the Middle Ages. It was an artisan craft.

As a result of these circumstances, things like spelling practices varied from one place to another, and one scribe to another. The same word could even be written on the same page in multiple ways.

All this began to change in the 15th century, however, with the introduction of the printing press, which allowed, for the first time, the mass production of writing. This coincided in France and England with the intellectual movement that we call the Renaissance: an attempt to revive the ideals and spirit of the classical world.

This spirit of the Renaissance meant not only a renewed interest in the Latin language and its literature, but also an attempt to “refine” the spoken languages to the level of sophistication (as they saw it) of Latin. The inconsistency of the medieval scribe seemed like a relic of the past to be jettisoned: a language’s spelling should be rational.

In England, the path to standardization was more complex. The era saw a wave of radical reform proposals from humanist scholars. Figures like Sir Thomas Smith and John Hart, for example, devised comprehensive phonetic alphabets that included new letters and even diacritics to mark long vowels.

Ultimately, however, these ambitious projects failed. England lacked a central authority, such as a royal academy, with the power to enforce such a dramatic break with tradition. So the reforms that succeeded in England were conservative, pushed by printers who chose to regularize the messy but familiar system they had inherited from those Norman scribes many centuries ago.

Where do diacritics come from?

In France, the course of history ran differently: the need for consistency brought on by the introduction of the printing press gave birth to diacritics.

The first diacritic to be used widely in French is the acute accent (´), which is used exclusively on the letter e: é. Its function is to distinguish between two different sounds spelled e: the sound of je ‘I’ (close to the unaccented a’s in the English word banana) and the sound of pré ‘meadow’ (close-ish to the English pray).3

The acute accent was introduced into French by the printer and humanist Geoffroy Tory in 15294 in his book Champ fleury, a combination of humanist allegory and typographical manual, which aimed to “decorate and illuminate our French language.”5

The shape of the acute accent was a direct product of the spirit of the Renaissance: Tory drew his inspiration from the editions published by the Italian humanist and printer Aldus Manutius, who had pioneered the printing of Ancient Greek texts using the system of accents developed for that language in the Roman period. One of these was the acute accent (Greek ὀξεῖα ‘acute, sharp’): in adapting this classical model for the needs of French, Tory (in his mind) elevated the vernacular language to the same level of sophistication as Latin and Greek.

Tory also introduced another familiar French diacritic: the cedilla (¸), found only on the letter c: ç. As I mentioned briefly earlier, the cedilla has the function of ensuring that a c can be pronounced like an s, despite coming before an a, o, or, u: for example, Français ‘French’, garçon ‘boy’, reçu ‘received’, pronounced with s-sounds rather than k-sounds.

The cedilla wasn’t originally French, however, or even Greek: it was a Spanish innovation dating back to the days of the Visigoths. It was originally a z, written first after a c, and eventually with the c stacked on top of it: Ꝣ.6 The name cedilla just means ‘little z’ — ceda is Old Spanish for ‘z’, the letter called zeta in today’s Spanish.

In Old Spanish, the c with cedilla wrote the sound ts, found in Old Spanish, e.g. çielo ‘heaven’, lança ‘lance’. Due to later changes in Spanish, this sound disappeared, being replaced in most of Spain with the th-sound and elsewhere with the s-sound. As the sound disappeared, so did the need to write it differently: today, these words are written with c (before i, e) or z (before a, o, u): cielo, lanza. The cedilla had been used sporadically in French manuscripts since the 13th century: Tory’s innovation was to print it, and to do so systematically.

Tory’s reforms took root because he wasn't just a local printer: he was, as of 1530, the imprimeur du roi, the official printer to King Francis I. This royal patronage gave his proposals immense prestige. Later, this top-down approach to language was formalized with the creation of the Académie française (French Academy), which officially adopted and standardized the use of accents in its 1740 dictionary, cementing their place in the language. It was a break with the earlier French tradition which had taken root in England: that new sounds would be written with extra letters.

This is the great paradox of French reform. The introduction of an entirely new mark was a radical innovation. Yet it often served a conservative goal: to preserve a word's traditional, etymological spelling while also acknowledging a shift in pronunciation. Rather than rewriting a word traditionally spelled Francais with an s to indicate how the c should be pronounced, the addition of the cedilla diacritic kept the traditional spelling largely intact, but for a little squiggle or mark here or there.

French would come to adopt other diacritics too, including the circumflex (ˆ), as in forêt ‘forest’, which marks a vanished consonant, and the diaeresis (¨), as in maïs ‘corn’, which marks a break between two syllables. These diacritics have interesting stories as well, which I’ll tell you another day.

But what they all have in common is that they were creations of the Renaissance, and very typical ones at that: like many of the products of that era, French diacritics combined classical inspiration (e.g., taking cues from the Greek accent system) with the modern impulse to systematize and rationalize. The result was the French system of spelling we know today: full of diacritic marks.

In England, on the other hand, what the Renaissance systematized was the status quo: the basic spelling patterns of English laid down by Norman scribes in the 11th century, which used combinations of letters to express different sounds.

In a way, it’s a shame, because English could really use some disambiguating marks between words like wind (the noun) and wind (the verb), lead (the noun) and lead (the verb). But situations like these are surprisingly few in English: English manages to soldier on without diacritics because we have found those Norman scribal practices sufficient.

The combinations of letters that so vexed our poor monk Godwin came to define English spelling. And it created a historical irony: when this very French custom of writing new sounds by adding extra letters became entrenched, it made English resistant to diacritics, one of the things that makes French so recognizably French today.

Another, less common, reason to use diacritics is to distinguish between two words that would otherwise be written identically. The French use of the grave accent (`) in à ‘to’ is an example of this use: otherwise, it would be written the same as a ‘has’. Similarly, où ‘where’ has an accent, while ou ‘or’ does not.

If you don’t believe me that these combinations each make a single sound, try saying only the first or last letter of, say, sh or th and see what sound it makes.

IPA [ə] and [e], respectively.

Some sources credit Tory with the inspiration only, and Tory’s friend Robert Estienne with the introduction of the acute accent in 1530.

“décorer et enluminer notre langue française”

The variant of z used was a tailed z: ʒ.

Another nicely written and informative essay.

Some editors were recently giving *The New Yorker* a hard time because they continue to insist on using the dieresis. The editor in me wanted to join in the jeering, but the contrarian wanted to applaud them for refusing to coöperate.

Absolutely fascinating! 😍