Why people fail at learning languages

And how you can do it better in 2026

Most people who set out to learn a new language fail.

It starts at school: in what other subject do we accept that the regular outcome of several years of study, under the guidance of professional teachers, is indistinguishable from not having studied at all?

There’s a reason that we’ve all heard (or said) something like this: “I took Spanish all through high school and all I can do is ask where the bathroom is”.

If that’s been your experience learning languages, you’re not alone. Learning languages is something we are really bad at, at least in the English-speaking world.

Once you’re out of school, the experience is no better. If you’re like a typical novice language learner, you’ve probably experienced the following sequence of events: you decide to learn a language, so you buy a book, register for a class, or download an app (you know the one I mean).

At first, you feel a sense of accomplishment: the first few words, maybe a phrase or two, emerge! You’re going around asking everyone where the bathroom is.

Over the next weeks and months, you spend lots of time, effort, and maybe also money, on these things. You’re getting the answers right in your book, you pass your class, and you’ve got a hundred-day streak on your app.

Then you meet a native speaker and try out your skills with a little conversation. And you soon realize that all the stuff you learned in class has vanished into thin air just when you needed it the most. Those verb conjugations you aced on the test are now nowhere to be found. And, even worse, you can’t understand half of what your new friend is saying: they just speak so fast!

It’s total conversational failure. You both switch to English after 90 seconds of pain.

What happened? You had learned everything about the language so well, and none of it was of any use to you when actually trying to use the language.

If you’re like most learners, you’ll conclude that it’s a hobby for other people, people who have talent at languages. You decide to take up an easier hobby, like sword eating or quantum physics.

But it doesn’t have to be this way!

The reason most language learners do so poorly is not because they are lazy, stupid, or because they lack the “talent” for language learning. It’s because we, as a society, have an inaccurate idea about what it means to actually learn a language. And this follows from an inaccurate idea about what language is.

Only when we truly understand what language is can we understand how not to fail at learning languages. And that’s what we’re going to talk about today.

Why should you listen to what I have to say about this? For starters, I’m a linguist, which helps with the “what is language” part of the story.

Applying that understanding to the practice of language learning, on the other hand, requires a different skill set, so here are my more practical bona fides: I’ve been learning languages (and reflecting on the process) for over 20 years,1 and I’ve reached a high enough level in two of them (Latin and Old English) to teach them professionally. I’ve even written the first graded reader for students of Old English.

What I write here is informed by this experience, but I’ve only got part of the story. What has worked for me (or for some of my students) may not translate perfectly to your life. So, rather than give you an exact prescription for what to do, I will give you three principles that you can apply in a way that suits your own situation and interests.

Much of this article is based on linguistics and second language acquisition research, but I’m going to keep this explanation, as much as possible, free of jargon and excessively cautious academic language. There are citations in the further reading section for those who want to learn more. But, for the rest of you, I’m going to treat this like an emergency intervention, and get straight to the point.2

Language learning is in crisis. But we have a way out. And it all begins with understanding what a language actually is.

You’re reading The Dead Language Society. I’m Colin Gorrie, linguist, ancient language teacher, and your guide through the history of the English language and its relatives.

Subscribe for a free issue every other Wednesday, or upgrade to support my mission of bringing historical linguistics out of the ivory tower and receive two extra Saturday deep-dives per month.

You’ll also get access to our book clubs (you can watch the recordings of the first series, a close reading of Beowulf), as well as the full back catalogue of paid articles.

What is a language?

Learning a language is unlike other kinds of learning.3 This is because knowing a language is not like knowing other things.

As a result, the tools and strategies you have used to learn other things (like brute force repetition of facts) may not apply, and the best way to learn a language will look quite unlike the best way to learn anything else.

To understand why this is, we first need to understand what language actually is — or, well, let’s start with what it is not.

A language is not primarily a collection of facts you have to memorize, nor is it primarily a skill you can improve at with practice. A language is both of these things too, but only in a secondary way.

What a language is, at root, is an abstract and unconscious kind of knowledge. You can compare it to the tacit knowledge about the world that optical illusions take advantage of.

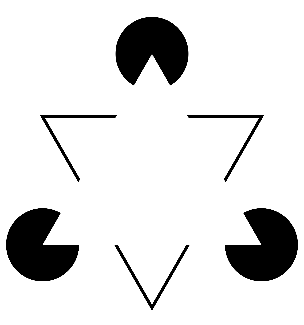

For example, in the Kanisza triangle illusion, we see a triangle in the centre of the image, even though there is, strictly speaking, no such triangle. There are only disconnected shapes which suggest the existence of a triangle:

This “contour completion” illusion rests on tacit knowledge that we have about how shapes tend to work in the real world. In the explanation given by the excellent website The Illusions Index:

It is generally accepted that contour completion is an example of the perceptual system rejecting ‘coincidence’, in the sense that a symmetrical arrangement of fragments and line elements as seen in the Kanizsa triangle is unlikely in the natural environment. A similar retinal stimulation is more often caused by one continuous surface occluding another, and so this is how the Kanizsa stimulus is represented by our perceptual system (Rock and Anson 1979).4

Knowledge of language, like knowledge of how shapes work, also leads to illusions. In fact, you could think of language as nothing but an illusion, the illusion that particular sequences of sound waves, or particular configurations of ink on a page,5 have meaning.

The goal in learning a language is to acquire so much of this tacit knowledge that the illusion becomes so strong that you can’t encounter these sounds or these symbols without associating them with a meaning. We call these sounds and symbols “words,” “phrases,” and “sentences.” And we give the name “understanding” to the illusion of meaning that results when we encounter them.

For certain sequences of sounds or symbols, which we call the words of our native language, the illusion has taken hold of us so strongly that we can’t help but bring their meanings to mind, even when we’d very much rather not, as happens in the case of schoolyard taunts and spoilers for television series alike.

We say, “I wish I could un-hear that!”, because we can’t imagine the idea that we could hear the words of our language and not have their meanings called to mind.

To have this illusion take hold of you, is, at its root, what it means to learn a language.

Normally we talk about this in the opposite way. We tend to say that you acquire the knowledge of a language. But turning things around and making the language the subject is an attempt to bring to the fore a distinction between the process of acquiring languages and the process of acquiring other kinds of knowledge.

Another important difference is that knowledge of language — unlike knowledge of world capitals or Roman emperors — is unconscious. Speakers of a language have access to mysterious feelings about what counts as a valid sentence in a language and what does not, but they don’t seem to know why some things work and other things don’t.

For example, if you didn’t hear what someone made for dinner, you can ask What did he make? But if you hear that he made ??? and eggs, you cannot ask 🚫What did he make and eggs?

Why not? It’s perfectly clear what is being asked here. Syntacticians have an answer, but if you ask a native English speaker who doesn’t happen to be a syntactician, he or she will just shrug and say, “It just doesn’t sound right.”

This spooky intuition that “it just doesn’t sound right” is the voice of the speaker’s unconscious knowledge of a language. It is the sound of the illusion breaking down.

All of this is what we’re trying to acquire when we learn a language. We can call this knowledge the mental representation of the language.

Yes, we also want the ability to speak in an unhalting manner. We want to be able to express ourselves as clearly as we do in our first language. We want to be able to pronounce words in ways that make us sound like we belong to the community of speakers of that language.

But all of this depends on the prior existence of a mental representation of the language.

I bring this up because it’s very common for language learners to bewail their lack of ability to produce the language, at least, compared to what they can understand. This is utterly normal. Productive ability always, always, always lags behind the ability to comprehend.

This asymmetry is there even in our first language: I am a native speaker of English, and as a result, I can read Moby Dick. But I doubt I could write anything as good as it.

So, as you review the strategies and tactics below, keep this in mind: what we are aiming for is the acquisition of the mental representation of the language. We want the illusion to take us.

The other parts of a satisfying relationship with a new language — the speaking, the writing — follow in the wake of comprehension.6

So how do you acquire a mental representation of a language, given that it’s tacit and abstract? It’s not like learning explicit facts.

This is where most of the strategies used by novice learners fail. They treat languages as sets of rules that you have to memorize consciously: this is an -ar verb, so it conjugates like this; this is a feminine noun, so it makes the adjective agree like this.

There’s lots of theoretical and experimental work out there examining this question. I’ll leave you some recommendations in the reading list below. In many ways, the exact process is still a mystery even to the scientists who research it. But we certainly know, in broad terms at least, how it works.

Here’s how it works.

More is more

If I could boil down all the advice I can give you into a single sentence, it would be this:

The core activity that builds up your mental representation of the language is decoding messages in the language.

Decoding messages means listening to the language, or reading it, in order to understand the message that is being communicated. Lots of things satisfy this criterion: reading books, watching TV and movies, listening to podcasts, even reading road signs all count. Conversation counts too, at least the portion of the conversation where you’re listening to the other person.

But just as many things count as decoding languages, many things do not. And, unfortunately, most of the things that novice language learners spend their time doing fall into this category of “not decoding messages.” So they spend lots of time doing what they think is learning the language, but don’t see corresponding results.

For example, the following activities involve decoding messages only minimally: reading textbooks, doing grammar exercises, studying flash cards, keeping up your app streak, and attending typical grammar-oriented language classes.

These things aren’t useless activities for the language learner, but they are mostly useless for building up your mental representation of the language. (I’ll get to what these things are useful for in a bit.)

And, what’s worse, these activities tend to be tiring, effortful and, in some cases, unpleasant.

To spend hours upon hours doing something hard without very much to show for it is a terribly dispiriting thing. It’s no surprise, then, that so many language learners give up so quickly, if their language learning diet consists mostly of classes, textbooks, and flashcard apps.

The tragedy of it all is that these are precisely the things novice language learners first attempt. But, after a few months of frustration, so many language learners conclude that it’s a hobby for other people, people who have talent at languages. But they’re wrong. Wrong, wrong, wrong. Language learning is for everyone.

Now we come to our first practical principle of language learning: the time-on-task principle. This refers to the entirely unshocking reality that, the more time you spend doing the core activity of learning a language, the quicker you’ll make progress.

This is the linguistic equivalent of “exercise more if you want to get healthier.” Everyone knows it: the problem isn’t in the knowing, but in the doing.

The major obstacle here isn’t usually laziness or a lack of discipline. The obstacle is that people often spend lots of time doing things that don’t work. As I’ve alluded to already, not every activity branded as “language learning” actually helps you build a mental representation.

We can call time spent on the right things the number of contact hours you have with the language.

Properly understood, language learning doesn’t even require you to reshape your life around it (very much). The time-on-task principle means that the more time you spend, the better off you’ll be, as long as you’re spending your time on the right things.

Change your life in 10 minutes a day, give or take

How much time do you need to spend to make progress? That seems to depend on a few different things, some having to do with the activities you’re doing and others having to do with your level in the language.

First, not all activities are equally beneficial for building your mental representation of the language.

An hour spent reading a book or listening to a podcast, for instance, is almost entirely devoted to decoding messages in the language. But an hour spent on a popular language learning app (which will remain nameless) will be more of a mixed bag. That hour may involve some time spent decoding messages in the language, but these messages will tend to be isolated sentences without context. “The cat is playing the piano.” This means that you’re reorienting yourself to a new situation every few seconds, which slows you down.

Language learning apps typically also have you spend time on other activities beyond pure reading or listening. For example, it may try to focus you on how a particular grammatical construction is used, or treat you to flash card-like activities where you match vocabulary words in your target language with words in your native language.

These sorts of activities have their place, as we’ll discuss shortly, but they are not a replacement for the core activity of language learning, which is decoding messages. So, instead of counting 100% of your time spent on the app as contact hours with the language, you might only count, say, 50%. So it will take you 10 hours of time spent in the app to get 5 hours of contact time.

All that is fine if you have vast expanses of free time on your schedule. But I somehow suspect you don’t.

Some activities are even worse: I’ve been in language classes where only about 5% of the time was spent trying to understand messages in the target language. Ten hours of a class like that would only amount to half an hour of contact!

But let’s assume that you’re making the best use of your time, and focusing on the most beneficial activities, so that every hour you spend learning the language is a full contact hour. How much time should you expect to spend in order to make progress?

Here’s my experience: I find that I can make steady, noticeable progress on a language with as little as five contact hours a month, as long as it’s a language in which I’m at more or less a beginner level.

(You may find you take more or less time than me: on the one hand, I am more or less a professional language learner. Then again, I am probably still doing some things suboptimally.)

To save you having to get out your calculators, that equates to ten minutes a day reading or listening to a language, itself a pretty pleasant activity. And, for that investment, your life changes and you start on the road to bilingualism (and beyond).

When I get beyond the beginner level in a language, I find that spending merely five hours a month no longer suffices to keep up the pace of progress. Instead, I seem to stay at roughly the same place in these languages which I know better. For them, I find I need around ten hours a month for the progress to continue at the same pace. If, by some miracle, I manage to spend 20 contact hours with a language in a month, I see dramatic improvements in my level, provided it’s not a language where I already have a very high level.

I’d recommend tracking the time you spend learning a language for a few months. Not only is it motivating to see the number go up (and to know it corresponds to real increases in your knowledge of the language), but it’s easy to deceive yourself about how much time you’re actually spending on things.

It’s easy to get discouraged about your lack of progress, saying something like “I’ve been learning Spanish for three months.” But if it’s only five contact hours spread out over those three months, and those hours were spent doing the wrong things, lack of progress is exactly what you should expect.

As you can see from my example, the amount of time needed to make progress seems to increase as you get better in the language. But it also becomes easier to spend that time as you improve: you can read (or listen to) more things — and better things — as your level in the language increases, and you gradually make the transition from a learner of the language into a speaker.

Now it’s time to talk about exactly what goes on during these contact hours, which brings us to the next principle: the principle of quality.

The most important thing is to ______.

Long-time readers will know that both quantity and quality are words whose existence in the English language we owe ultimately to Cicero. They are ultimately Latinizations of Greek words meaning roughly, ‘how much-ness’ (< quantum ‘how much; how great’) and ‘what kind-ness’ (< qualis ‘what kind’).

In our quest to understand how best to study a language, we began with the “how much” question, which we answered with “as much as possible.” We can now proceed to the “what kind” question, to which we’ve outlined a solution already: your study of a language should centre on the decoding of messages in the language, that is, listening to or reading content written (or spoken) in the language.

Because it gets awkward saying “listening to and reading” over and over again, let’s use what some of you may consider to be a barbarous word: consuming. And, instead of saying “content written (or spoken) in the language,” let’s say input.

So your task is to consume input. But the quality question still haunts us: what kind of input?

Ideally, you want it to be interesting. But intrinsic interest isn’t the only factor to consider. I don’t, for example, recommend a novice French learner begin with Les Misérables, nor would I counsel a Mandarin neophyte to pick up Dream of the Red Chamber.7

Anyone who has watched language learning videos on YouTube is probably shouting at the screen right now, waiting for me to say the magic phrase: comprehensible input. There, I’ve said it: the input you consume for the purposes of building your mental representation of the language should be comprehensible.

This may sound obvious. If what’s in front of you is functionally gibberish, how could you learn it? Of course the input has to be comprehensible! But it’s actually a bit subtler than that. If what’s in front of you is completely comprehensible, as if it were written in your first language, there’s probably not much left for you to learn from it.

Instead, what comprehensible input means in practice is that you’re looking for content where you’re in a Goldilocks-style sweet spot. Ideally, you’ll be able to understand the message being conveyed without understanding every word and bit of grammar in that message. As you consume this input, your mind get to work behind the scenes, building up a mental representation of the language, which includes not only the meanings of individual words, but also the more abstract and mysterious features of grammar.8

This process of working out what new forms must mean on the basis of context is more or less how your vocabulary grows in your native language: for example, when you see an unfamiliar word within a passage you otherwise understand well, you can usually triangulate the meaning of the new word using clues from the context you find it in.9

But this is only possible given an adequate understanding of the context. If the ratio of unknown-to-known items in a passage drops below a certain threshold, it’s no longer possible for you to work things out. The drop-off is quite sudden, and seems to occur somewhere around the 90% comprehension level. In other words, understanding ninety words in a hundred-word passage is insufficient to let you guess what the remaining ten words mean.

You can get an idea for what various levels of comprehension feel like by manipulating passages of English. Blanking out one word of a hundred-word passage shows you what 99% comprehension feels like. Blanking out ten gives you the feeling of 90% comprehension.

So let’s do an experiment to build up your intuitions about comprehensibility. Here are four passages of English, with different numbers of words removed, not at random, but focusing on the least common words. This matches the experience of second-language learners, who typically learn words in rough order of frequency. At what point do you stop being able to guess what the missing words might be in each passage?

99% comprehension

Countless writers have dwelt upon the taking of human life; some of them were rather commercial gentlemen who always gave an ear to the demands of their public, and their ______ were written for the money that they would put in their pockets; but others, and by long odds the greatest, were fascinated by their subjects. Both Stevenson and Henley were powerfully drawn by deeds of blood. Did you know they planned a great book which was to contain a complete account of the world’s most remarkable homicides? I’m sorry they never carried the thing out; for I cannot conceive of two minds more fitted to the task.10

95% comprehension

“Mrs. Dwyer is _________ paid to clean only the hall and lower stairway,” replied Ashton-Kirk, composedly. “And that she sticks closely to that arrangement is shown by the _________ of this upper flight. The dust upon the step is rather _____. If you will notice,” and he indicated a place on the second step, “here is a spot where a _____, flat object rested. That this object was a silk hat is positive. You can see the sharp impress of the nap in the dust; here is the ____ in the exact center of the crown as seen in silk hats only. And men who wear silk hats are usually well-dressed men.”

90% comprehension

“But there will be a _____,” said his friend. “And that may be what we need just now. Perhaps a few hours will mean _______. You can never tell. The best that we could get by __________ matters to Sime would be a ________ ______________ of Spatola, or the _______. And we can get that from him at any time. So you see, we lose nothing by waiting.”

“I guess that’s so,” Pendleton ____________, and again the car started forward. At the huge entrance to a ________ station they drew up once more.

Within, Ashton-Kirk ________ for the _______ _________ Agent and was directed to the ninth floor.

75% comprehension

“You say that the _______ of the ____ shows the person who ____ the ____ to have been ____________ with the place. I think you must be ____ here. Spatola is __________ with the place; he was here at the time. This is ______ by the ______ of the __________ ________ which followed the _______ of the ____.”

“It was not a ________ that made the _____,” said Ashton-Kirk. “Give me a ______ and I think I can _______ you of that.”

The ___ in the ____ was _______; the ____________ _______ at the ____ of the ______ leading to the ______ ____.

If you’re like most people, your ability to understand what is going on in the 90% and 75% comprehension passages is severely impaired.

As much as possible, you want your experience with the language to feel like the 99% and 95% comprehension passages above rather than the 90% or the 75% comprehension passages. This is what is meant by input being comprehensible.

Of course, you need to start somewhere. In the first phase of your learning, nothing aimed at native speakers of the language will be in any way comprehensible to you. You must therefore seek out materials directed at learners. This can be simplicity itself or a significant challenge, depending on the language you’re learning.

One of the benefits of having real, live, humans to speak to in the language is that they will — if they’re patient enough (or you’re paying them to do it) — adjust their language such that you can understand it. If you don’t have people to talk to (or all the qualified people are dead — this is the Dead Language Society, after all. Some of you may be all jazzed to learn Sumerian!) you’ll need to rely on written or recorded material.

If you’re a relatively inexperienced language learner, you may want to skip Sumerian for now in favour of Spanish, or another language with lots of good resources for learners.

Look for graded readers: these are books written with a limited vocabulary, so that learners have an easier time. Another option, in the earliest days, is to power through incomprehensible input. But this requires a lot of patience and active engagement.

That said, the very initial stages of language learning are often accompanied by a burst of motivation, so you are more likely to be willing to put up with suboptimal material for a while. And by the time that wears off, you’ll likely have a few hundred words under your belt, and you may find that the material which had been too hard had become, like Baby Bear’s porridge, just right.

Ownership

“Is that it?,” you may be asking. “You just do fun things like reading books and watching TV in the language, and eventually you get to a point where you speak the language?”

Well, yes. Sort of.11 I’m not done yet, remember. I still have one principle left to show you: the principle of ownership.

This is the principle that I’ve come to understand most recently, as a direct result of teaching and developing curricular materials.

I’ve found that simply consuming input — even when that input is comprehensible — seems to result in an excellent ability to comprehend, but a frustrating lag in the ability to produce. As I mentioned earlier, it’s entirely normal for production to lag behind comprehension.

But what you don’t want is for that lag to become a matter of frustration for you. Frustration leads to spending less time with the language or to quitting altogether.

I’ve found that this frustration tends to be alleviated by activities that give you a sense of conscious “ownership” of what you’ve already been acquiring unconsciously. Paradoxically, these include the very activities that I said were not effective at building up your mental representation:

creating flash cards,12

explicit grammar learning (reading books explaining grammar to you)

doing composition exercises (e.g. turn this sentence from the active to the passive voice).

What do these things have in common? They all involve primarily conscious processes, and attention to the form of the message rather than its content. Exactly the things that don’t build up your mental representation.

This is why I once said things (to myself) like, “Don’t make flash cards! They’re not worth the trouble.” But I’m now convinced that I was wrong about this, and I’m proud to say that I’ve maintained a consistent flash card habit for the past 4 months. Please clap.

What are these activities doing for you? Each is probably doing something different, but I group them together because I think they have one thing in common: they make you feel comfortable as a participant rather than a spectator in the linguistic community.

The trick, however, is understanding the proper place of these activities in your learning practice. They are not the primary means by which you acquire knowledge. They should be applied only to things that you already understand well. And how do you come to understand things well? By consuming lots of input.

Think of these ownership strategies as multivitamins, and the consumption of input as your main course. Vitamins are great, and sometimes you need to supplement your diet with a multivitamin. But if you’re consuming primarily vitamins, something has gone wrong.

Most novice language learners end up in situations where they’re eating nothing but multivitamins and wondering why they’re starving. They would do much better starting off with a programme of listening to and reading easy material in the language for six months, and only then progressing to the apps, classes, and grammar books.

So there you have it, three principles to guide your language learning in 2026:

Time on task. The more of the right things you do, the faster you’ll make progress.

Quality. The right thing is consuming input at roughly a 95–99% comprehension level.

Ownership. Supplement your input with explicit study of vocabulary and grammar when you start to feel frustrated that you can’t produce things you already understand.

If you’ve been a frustrated language learner so far, I hope that 2026 is the year that changes for you. It is possible for you — for basically anyone — to learn another language, with the right tools and understanding. And it’s one of the most rewarding experiences you can have.

Reading List

To keep this article practical, I’ve avoided talking too much about second language acquisition research here. But many of the suggestions I’ve given in this article are in fact based on this research. Like any academic subject, there’s good and bad stuff out there. If you want to learn more about it, I recommend starting with a guide. Use one of the following books, which were written not for researchers but for language teachers or students.

Henshaw, Florencia and Maris D. Hawkins (2002). Common Ground: Second Language Acquisition Theory Goes to the Classroom.

VanPatten, Bill, Megan Smith, and Alessandro G. Benati (2020). Key Questions in Second Language Acquisition.

If you prefer to get your information in audio or video form, the first author of the Key Questions book, Bill VanPatten, has several lectures and interviews available on Youtube. He also happens to be hilarious, which helps. This playlist is a good place to start.

How many languages do I speak? It’s a hard question to answer, since what counts as “speaking a language”? But I have studied, to varying degrees of proficiency, French, German, Spanish, Latin, Sanskrit, Russian, Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Korean, Mandarin, Classical Chinese, Yiddish, Old English, Ancient Greek, Biblical Hebrew, and Old Norse.

At least, as straight to the point as my editor can make me.

Some second language acquisition researchers distinguish between conscious learning and unconscious acquisition of a language. I use the term learning in this article, but if you’re keen on that distinction, do a mental find-and-replace and turn every instance of “learning” in this article into “acquisition.”

Thomson, G. and Macpherson, F. (July 2017), “Kanizsa’s Triangles” in F. Macpherson (ed.), The Illusions Index. Retrieved from https://www.illusionsindex.org/i/kanizsa-triangle.

Or pixels on a screen.

That’s not to say that you can’t work on these productive skills as you’re improving your comprehension. You can and should, but, generally, you can’t learn to produce a word, phrase, or bit of grammar you don’t already comprehend well.

It would be a crime to mention this book on Substack without directing you to Daniel Evensen’s excellent Dream of the Red Chamber project.

My editor would like to share how much this has helped her, particularly with grammar. She is an avowed hater of grammar study, and rebels whenever she is forced to do any. Explicit grammar instruction has done nothing but frustrate her, but over time, as as her mental representation in the language grew, she started to get a sense of (for example) where to use the dative case in German because it “just sounded wrong otherwise.” This is what the development of tacit knowledge of language feels like. You know that something feels right or wrong but you can’t necessarily explain why.

You often have access to other clues as well, such as the existence of related words and the meaning of the parts of the word (e.g. an English word ending in -ation is probably a noun).

Passages drawn from John T. McIntyre, Ashton-Kirk, Investigator.

Basically everyone in the second language acquisition world believes that consuming large quantities of comprehensible input is a necessary condition for acquiring a language. But there’s some controversy out there in the second language acquisition research about whether input alone is sufficient for language acquisition. Many scholars believe that input must be supplemented with something else. Frustratingly, many people (especially on Youtube) use the phrase comprehensible input to refer to the idea that comprehensible input is necessary and sufficient. This is inaccurate: comprehensible input is a construct, not a theory, and, as a construct, it’s not controversial. What is controversial is the idea that comprehensible input is the only thing necessary for acquisition (which forms one part of Stephen Krashen’s Input Hypothesis). End rant.

The word “creating” is, in my mind, the most important part of “creating flash cards”. I think that the ownership comes primarily from the creation of the flash cards rather than the reviewing. But I’m still exploring this question. Clearly reviewing flash cards also has some value, but I suspect the value depends largely on the format. For example, flash cards with a word plus an example sentence on the front seem much better than flash cards with a word alone on the front. Why? I believe that the benefit of the sentence card is mainly that it makes you reread sentences you’ve already comprehended once, and start to move them from passive comprehension to a kind of automaticity. They turn into the equivalent of lines from your favourite movie, which you can quote verbatim at the drop of a hat. And automaticity underlies the ability to produce easily and without frustration. But, as you can see, this is a complicated question.

Thanks, Colin!

Your word "ownership" reminds me of something I've seen among flash card enthusiasts. Experienced language learners who use flash cards for learning languages just about always (in my experience) swear by handwritten cards, though they all have a different stated reason for it. (This is less true of medical students, who love their Anki decks.) I'm not saying that any of those reasons are wrong. It's probably very true that it's good to engage your muscles in learning a language, and that it's great to be able to easily use various colors and sorting methods. But it seems to me also that when you hold a flashcard in your hand that you yourself made, and see a word in your own handwriting, you have tangible proof that at least for a moment you knew it. The card confirms your ownership of the word.

Having said some nice things about flashcards, though, I also want to spotlight what you said here: "Most novice language learners ... would do much better starting off with a programme of listening to and reading easy material in the language for six months, and only then progressing to the apps, classes, and grammar books." Taking several months to do only comprehensible input was my 2025 strategy for Old English, and I'd vouch for it, even as I admit that it built up a surprising appetite for grammar. As I said to our mutual friend Logan, "Grammar is more fun like this than it is in the world of grammar/translation — it's more like being a natural historian trying to determine which squishy tide-pool creature you're looking at, and less like you're arming yourself with grammar tables in preparation for doing battle with the lines."

In fact, I've been recognizing many parallels between learning language and learning the natural history of a place, not least of which is that there's a surprising amount to be gained by just getting out there and looking around. Part of the natural-history game is to let your attention become attuned. Wandering around looking at things doesn't have the trappings of rigor, but one day you realize you know an awful lot that you didn't even notice yourself learning.

Thanks for another great article. A few thoughts:

Multiple things are necessary for learning a language to a high level. Right now "Comprehensible Input" is the "one neat trick" of language learning on line. somewhat like that special berry that if you eat two cups a day you'll lose fat and gain muscle. Sure, it helps a lot. However, at some point you need to do more than consume content to progress. There is no one neat trick. I'm currently at that step with Latin. I still consume a lot of content. But when I found that I wasn't progressing, I spent a month translating some Livy into English every day. I've seen my ability to read classical Latin improve noticeably. YMMV.

Another thing which you don't talk about (maybe it's obvious) but people have very different skills with language acquisition. So, while we can agree that memorizing declensions and conjugations as an initial focus isn't helpful, what comes next varies. And knowing the grammar helps certain folks (like me).

I've learned two languages to conversational fluency - Hebrew and French. (I maintain my Hebrew, my French knowledge is primarily passive right now). In both scenarios, I had friends who had much better "ears" for the language -- they sounded native. When it came to knowing the subjunctive in French or parsing a piece of Talmud, I really excelled. I find grammar to be cool. I have learned to speak and develop an accent that's not obviously American. When I speak the language, folks don't switch into English. It was a much longer process.