How the alphabet began

And some Dead Language Society lore

Early last week, this newsletter passed a milestone: the Dead Language Society is now more than 10,000 strong! Apart from saying how grateful I am that you’ve invited me into your inbox, I thought I’d take this opportunity to write a little about why this newsletter exists.

The Dead Language Society is — more literally than you might expect — brought to you by the letter ‘A.’

Now, of course, I need all 26 letters of the alphabet to write this newsletter (and often even more than that), but ‘A’ will always be special to me because it’s the reason I became interested in linguistics in the first place.

It all began with a big set of volumes of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, 14th edition, the kind that you’d buy from a door-to-door salesman in the 1960s. In fact, that may have been where this set came from, many years before I first encountered it as a young boy.

At the time, I wasn’t exactly sure what made an encyclopedia (or encyclopaedia, even) different from the storybooks I’d read thus far. So I did what I’d do with any other book: pulled down the first volume, set it on the floor of the playroom, and started to read from page 1.

The encyclopedia started with a bang, telling the story of the letter ‘A.’

I had always assumed that ‘A’, along with all the other letters I’d learned to sound out not so long ago, was part of the fabric of reality, much like the trees, rocks, and rivers. But now I was learning that ‘A’ had a history. It had changed over time. The ‘A’ that I used to spell A-P-P-L-E came from a group of people called the Romans. It was actually their ‘A.’

But then I read on… it wasn’t really the Romans’ ‘A’. They had gotten it from the Greeks, who called it alpha. And the Greeks had gotten it from another group: the Phoenicians (a name I didn’t attempt to pronounce for a long time afterwards). And the Phoenician version of ‘A’ or alpha was called aleph and it looked a bit weird: 𐤀. As it turns out, the Greeks had put it on its side (what we today deem to be the right way round) after they got their hands on it.

But I was soon to learn that the Phoenicians didn’t even come up with the letter ‘A’! It was Egyptian all along: a drawing of an ox’s head 𓃾, at least according to page 1 of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

And, you know what, I could see it in the 𐤀, and even in our ‘A.’ Yes, it had gotten a bit stylized over the years, but ‘A’ was kind of like an upside-down ox’s head!

By this point, I had questions: first, who were these Romans, Greeks, Phoenicians, and Egyptians? But, more pressingly, did the other letters have stories as well?

They did!

I whiled away many a happy hour tracing the evolution of the rest of the letters from ‘B’ — originally from the floorplan of a house, 𓉐 in hieroglyphs, 𐤁 in Phoenician — to ‘Z,’ from Phoenician 𐤆 zayn, whose ultimate origin still seems to confuse people today.

By the time I had written out the full chart of the origin of the alphabet, my curiosity was satisfied, but only momentarily. I still had another question to investigate: who were all these people whose alphabets we had pilfered? I started with the “Romans.”

As it turns out, the Romans were quite a big deal. But even more interesting than their military feats was the fact that their language, which was for some reason called Latin rather than Roman, didn’t just die out but evolved into other languages — including French, the language that everyone told me I’d be learning when I got to Grade 4.1

So not only did the alphabet evolve and change over time, but languages changed too! When I realized this, my fate was sealed. I would become a linguist and get to the bottom of how all this happened.

As it turns out, you can’t just become a linguist when you’re 11, so I did the next best thing, and I started learning every language I could get my hands on. The opportunity to learn French was handed to me on a silver platter, but I sought out other opportunities, trying my hand at German, Spanish, Arabic, Latin, Japanese… I even attempted Sanskrit at one point.

Some of these languages have become my constant companions later in life. Others — in particular, the ones more distant from English — didn’t stick very well at the time. I didn’t do a particularly good job of learning, since I didn’t yet know how to learn languages. But it kept me busy until I could “become a linguist,” which I could only do once I got to university.

So when the time came, I chose the University of Toronto, which offered not only a good linguistics programme but also a sufficiently broad selection of languages to learn. I was like a kid in a candy store. I picked up courses in Russian, Irish, and Scottish Gaelic, but it was the linguistics courses themselves that provided the most fuel for my intellectual fire.

In fact, one of the courses I took led me all the way back to my roots: it was called Writing Systems, and was taught by Henry Rogers. He also happened to write the textbook for the course.2 It taught me a much fuller version of the story told in my Encyclopaedia Britannica of how the alphabet came to be.

You're reading The Dead Language Society. I'm Colin Gorrie, linguist, ancient language teacher, and your guide through the history of the English language and its relatives.

Subscribe for a free issue every Wednesday, or upgrade to support my mission of bringing historical linguistics out of the ivory tower and receive two extra Saturday deep-dives per month.

This Saturday, we’re exploring how to write Old English-style alliterative verse in Modern English by analysing the works of the master: J. R. R. Tolkien.

Where the alphabet comes from

Here’s how the story goes, at least in the version I heard in 2005.

Almost all writing systems in use in the world today descend from one of two ancient systems: Egyptian hieroglyphs or Chinese characters. Thanks to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, we already know that our Latin alphabet descends ultimately from Egyptian hieroglyphs.3

At the time of that class, there was some debate over whether Egyptian hieroglyphs were inspired by the Mesopotamian cuneiform script. Our professor believed that the two developed more or less simultaneously around 3500 BC, although there may have been some mutual influence between them as they developed.

Egyptian writing, however, was not an alphabet. The term alphabet actually has a rather precise meaning when you get into the history and structure of writing: in Rogers’ words, an alphabet is “a type of writing system in which each symbol typically corresponds to… a consonant or vowel in the language.”4

The Egyptian writing system was much more complicated than an alphabet. It was a mixed system: some hieroglyphs wrote single consonants, others wrote sequences of two or three consonants, while still others wrote words5, similarly to how we sometimes write the word and with the ampersand symbol ‘&.’

Crucially, the Egyptian system did not write vowels: so the sequence written nm could mean ‘be firm,’ ‘be ill’, or ‘a sick man.’ Presumably, these had different vowels between or around the two consonants nm, but the writing system doesn’t record this. And, even more confusingly, the same hieroglyph could be used either for its sound or its meaning.

So to help out the poor reader, Egyptian scribes included extra hieroglyphs alongside the ones that represented sounds and words to help distinguish between the different possible ways of reading them. These were called determinatives.

Let me give you an example using emoji to stand in for hieroglyphs. How do you read the emoji 👁️?

You could be using it to represent its meaning, that is, to write the noun eye. Or you could be using 👁️ to represent its sound, that is, to write the pronoun I, as in 👁️♥️🐑 (either I love you or eye heart ewe.) This is called the rebus principle.

To make it clear that you were using 👁️ to represent I, you could put an emoji of a person next to it: 👁️🧑. Now, with the 🧑 determinative, you know that 👁️🧑 represents I, not the body part. You could do the same with 🐑 to save yourself the embarrassment of being understood as saying I love ewe: 👁️🧑♥️🐑🧑.

That’s how the Egyptian system worked. What came next was a radical simplification.

Ths sn’t tht hrd t rd, s t?

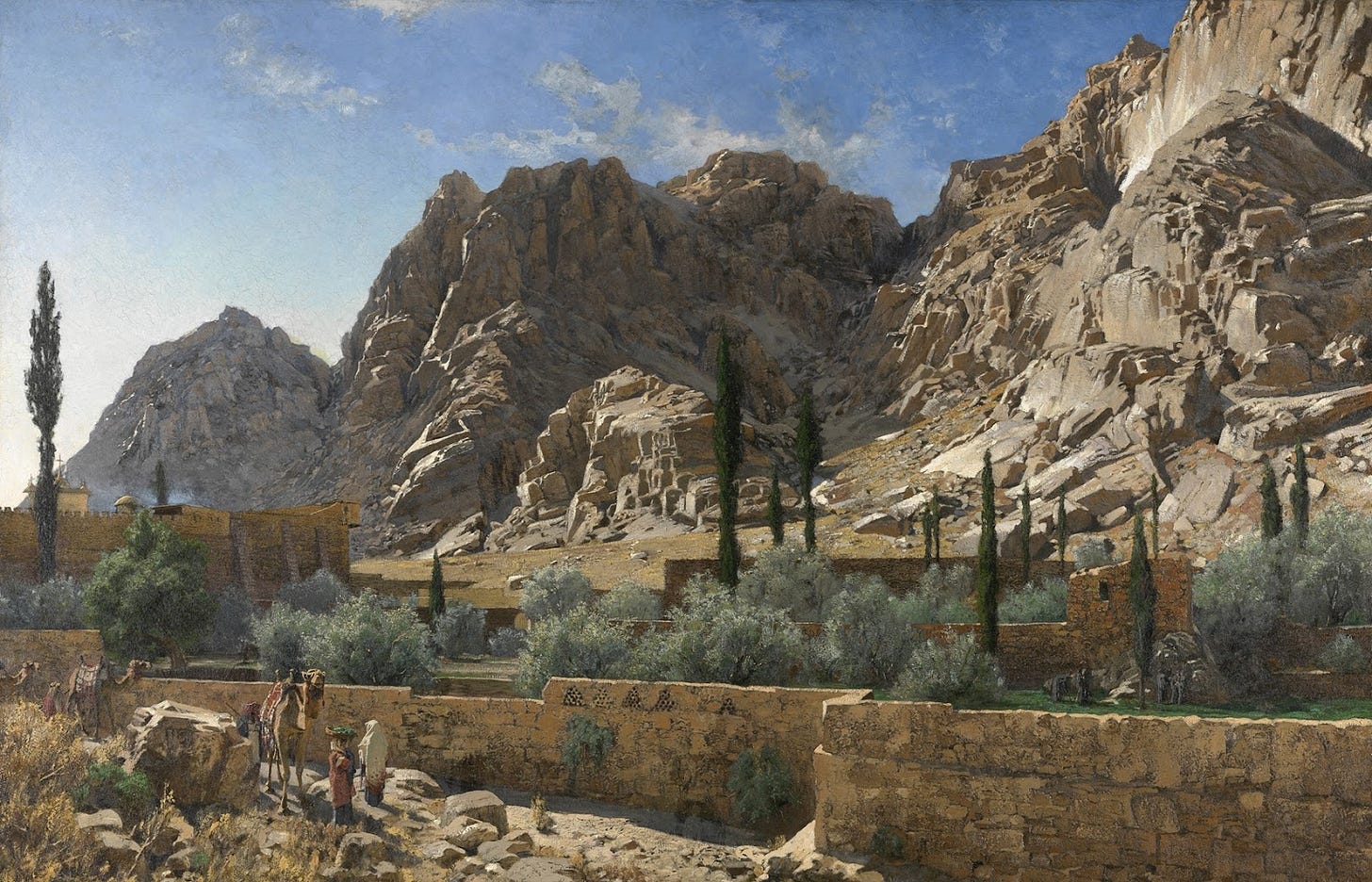

According to the story in my Encyclopaedia Britannica, the Egyptian system was drastically modified around 1700 BC by Canaanites, speakers of Semitic languages in the Levant, the eastern end of the Mediterranean. The writing system that first developed as a result is called by scholars the Proto-Canaanite or Proto-Sinaitic script.

The Levant was situated between the birthplaces of two great ancient writing traditions, the hieroglyphic system of Egypt to the west, and the cuneiform systems of Mesopotamia to the east. So in theory, the Proto-Canaanite script could have taken some inspiration from cuneiform writing.

Rogers told our class that there was still some lingering controversy surrounding the ultimate origins of the Proto-Canaanite script, but that the story hinted at in my Encyclopaedia Britannica was the most likely.6 In other words, the Egyptian script was modified to create something new.

And this something new was drastically simplified: out of the complex system of Egyptian hieroglyphs, the Semitic script was born as an abjad.

An abjad is a writing system in which symbols correspond to consonants. Vowels are typically not written in an abjad. This is similar to how part of the Egyptian system worked, minus all the multi-consonant symbols, the symbols that wrote words, and the system of determinatives.

The Semitic innovation was to take Egyptian hieroglyphs and adapt them to refer only to the first consonant in that word, that is, as it sounded when translated into their language.

For example, the hieroglyph 𓉐 could mean either ‘house’ or the two consonants pr, which is how ‘house’ was pronounced in Egyptian.7 But for the Canaanites, the word for house was not pr but bayt, which began with a ‘b’ sound.8 So, for them, 𓉐 represented the ‘b’ sound.

The Phoenician system that ultimately gave birth to English was an abjad too, as are the other systems that came from the Proto-Canaanite writing system, such as the Hebrew and Arabic alphabets, which are — now you know — not actually alphabets at all, technically speaking.

It took the Greeks to make an alphabet.

Finally, we get to the alphabet

Semitic languages, such as the Canaanite languages (one of which is Phoenician), could be written only with consonants without too much difficulty. Semitic languages are written this way to this day.

This is likely because the core root of words in Semitic languages consists of the consonants; it is not so with Greek (and most languages), where the root of words also consists of the vowel in the word.

So if we change the vowel in dog to make dig, we’ve now got an entirely different word, not just a modification of dog.

English largely works this way, as did Ancient Greek. So writing the vowels was a matter of greater importance to the Greeks than it was to the Phoenicians. And, as it happened, the Phoenicians had some letters left over in their abjad that represented consonants the Greeks had no use for. The solution: repurpose those letters to be used for vowels!

At least that’s one sensible version of the story: in truth, we don’t know why the Greeks came up with the idea of writing vowels when they began writing with their adapted version of the Phoenician script in the 8th century BC.

Whatever the reason, the first true alphabet was born! This Greek alphabet existed in various versions over the centuries and throughout the Greek-speaking world. One variant of the Greek alphabet made it to Italy, where it was adapted for use to write Etruscan, an ancient language of northern Italy.

The Etruscans’ neighbours, the Romans, further modified this already-adapted version of the Greek alphabet and used it to write their language, Latin. Their Latin alphabet travelled along with the form of Christianity later practised by the Romans: and wherever the Roman form of Christianity spread, the Latin alphabet came along for the ride.

As a result, the Latin alphabet is now used to write not only the languages that descended from Latin, such as French, Spanish, and Italian, but also languages much more distantly related to Latin, such as English.

Hearing the full version of that story so many years after first encountering it in the pages of the Encyclopaedia Britannica in my basement was exhilarating: I felt like I finally understood one of the mysteries of the universe that had first captivated me as a child.

Because I needed more mysteries to solve, I ended up going on to pursue a doctorate in linguistics, and studied all manner of strange things along the way. Perhaps I’ll share some of those with you another time. But my first linguistic mystery — where the alphabet came from — will always have a special place in my heart.

So if there are any parents reading this, take heed: watch what you leave within arm’s reach of young children. If you’re not careful, you could end up creating a future linguist.

The benefits of a Canadian education.

It’s still in print, by the way. Writing Systems: A Linguistic Approach. One of the most charming things about the book is that Rogers uses OLD and NEW rather than BC/AD or BCE/CE.

By the way, I also learned at university that the proper term is hieroglyphs, not hieroglyphics.

Writing Systems: A Linguistic Approach: p289

Technically, these hieroglyphs wrote morphemes, which can be smaller than a word: think of un- and -able in unbelievable.

Twenty years later, this is still where things stand.

You already know a word that has this pr in it: pr ꜥꜣ ‘great house,’ or English Pharaoh. As for how to pronounce it in Egyptian… It’s complicated. If you know the International Phonetic Alphabet, Wiktionary reconstructs the pronunciation */paɾuwˈʕaʀ/ for around 1700 BC.

You know a word with a descendant of Canaanite bayt ‘house’ in it too: Bethlehem, from Hebrew בֵּית לֶחֶם bēṯ lɛ́ḥɛm, literally ‘house of bread.’ A version of this root is still the Hebrew word for house.

The idea that modern writing scripts trace to either Egypt or China stopped me in my tracks, but a quick tour through Wikipedia tells me it’s basically true!

However, based on my memory, I can count one exception. The Cherokee syllabary was invented by a single illiterate individual in the 19th Century.

I remember learning the origins of the letter A as a child too and being thoroughly fascinated by it as well! And I've learned languages where I can too - French, German, Latin, Spanish, Japanese, a bit of Welsh, random bits of Romanian... I loved learning the writing system in Japanese too, which is partly what interested me, and the chance to learn a non-European language.

I've gone deaf, annoyingly, so I've been learning British Sign Language and it's fascinating - in some ways, it draws on symbols like Chinese, in that you sort of show/mime the "thing". Others involve a bit of finger-spelling (but you could never finger-spell a whole language - it'd take forever).

A really interesting example are the signs for silver and gold. They begin with either a finger-spelled g or s, then both are followed by a sign which involves sort of waggling your fingers to signify something sparkly. Isn't that ingenious? And all invented by Deaf people!

Sign languages have their own grammars, so BSL puts the question word at the end of the sentence - just like I was used to doing in Japanese. But there's even more to sign than that because if you ask a question, you lean forwards and raise your eyebrows to signify it's a question! It's so fascinating to learn, but also bloody useful when I'm struggling to follow what someone's saying. In fact, my youngest brother is selective mute and although he won't verbalise, he's being taught sign so for the first time in years we can talk to each other! Pinker's theory of "the language instinct" is potent.