The dead language tier list

What I learned studying 7 historical languages

It’s a new year and, as usual, people have all sorts of weird resolutions.

Some have resolved to run a marathon in 2026. Others are finally going to finish that novel they’ve been working on.1 Still others are going to slow down and learn to appreciate the beauty in the small moments of life, like the first ray of sunshine cast through their bedroom window on a lazy Saturday morning.

Like I said, people are weird.

But you had to come up with something even weirder, didn’t you? You want to learn a language. Worse, you have this crazy idea that it might be fun to learn a language that no one even speaks anymore.

No, no, you protest. It’s not you. It’s a friend. Sure, a “friend.” Whatever you say. Send them this article then, because they’re about to go on the linguistic equivalent of the Oregon Trail.

My job is prevent you — I mean, your friend — from dying of dysentery along the way

First, know this: Language learning is hard, whether the language is living or dead. Most people who try to learn living languages fail, for all sorts of reasons.

With dead languages, the odds of success are even slimmer. Unless you hang around with a very particular crowd, you’re unlikely to find conversation partners. And, unless you have a time machine, you can forget about travelling for immersion.

I don’t want to scare you. You can do it, especially if you have the right resources. But, just as important as your learning materials is your attitude. Any language — especially a dead language — is going to require years (plural) of sustained effort before you get to the point where you are able to read books in the language, or pass for a Roman senator, or whatever else you want to do.

And it is worth it. Being able to communicate with those who have been dead for centuries or even millennia, and to begin to understand their lives and world in their own terms, is a joy like few others.

But let me suggest to you that not every dead language2 is an equally good place for you to begin. Take it from me: I’ve studied seven dead languages now, each of which I’ve studied for at least a year. In the case of two of them (Latin and Old English), I’ve also reached a level where I can teach them professionally.

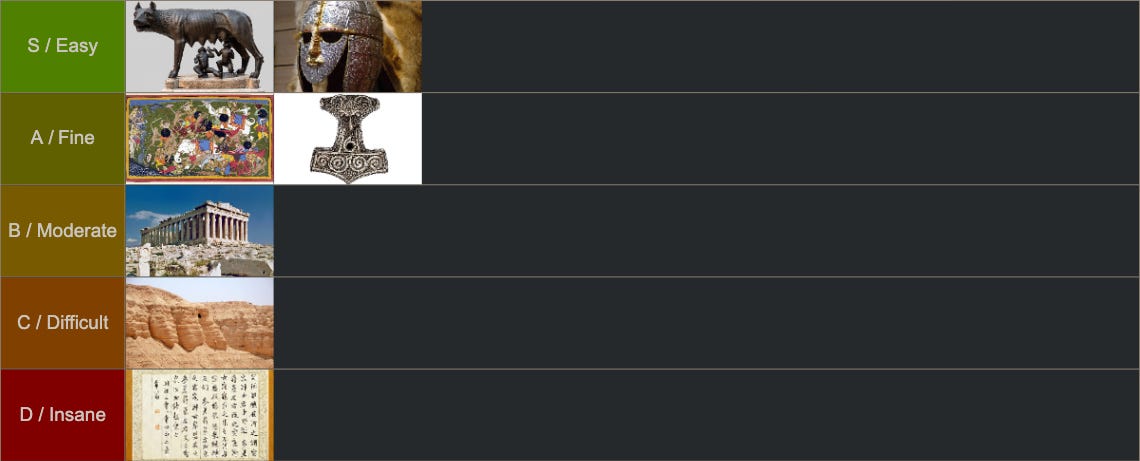

This tier list is a record of my experience in studying each of the seven languages, a record of my joys and sorrows as I’ve persevered through all manner of adversities in trying to, for lack of a better phrase, get good.

In coming up with the tier placements, I considered both the intrinsic ease of learning the language (assuming you’re starting from an English-speaking background), as well as the quality and quantity of resources available to learners. And, of course, all this is somewhat subjective.

My ratings aren’t a statement on the value of the languages. Each of these languages is a precious gift, and each is worth every minute you might spend on it!

Now for the list, in order from easiest to hardest.

You’re reading The Dead Language Society. I’m Colin Gorrie, linguist, ancient language teacher, and your guide through the history of the English language and its relatives.

Subscribe for a free issue every other Wednesday, or upgrade to support my mission of bringing historical linguistics out of the ivory tower and receive two extra Saturday deep-dives per month.

You’ll also get access to our book clubs (you can watch the recordings of the first series, a close reading of Beowulf), as well as the full back catalogue of paid articles.

1. Latin

Latin is a language, as dead as dead can be,

It killed the ancient Romans, and now it’s killing me.

-Anonymous

Latin is practically synonymous with “dead language.” It’s without a doubt the most popular ancient or medieval language to learn, at least in the English-speaking world.

It also has a bit of a reputation as a hard subject. Which is why it may surprise you that I’ve listed it here as the easiest dead language to get started with. Part of the reason for this is that Latin has lots and lots of good resources (which we’ll discuss in short order). But the sadder part is that, even though Latin can be a challenging language to learn, the others… are worse.

The biggest reason for Latin’s fearsome reputation is that it’s a heavily inflected language, meaning that words appear in lots and lots of different forms.

Nouns have different forms depending on their function in the sentence: one form for the subject of the sentence (the dog chases the cat), one form for the direct object (the cat chases the dog), one form for possessors (the bone of the dog), and so on. These different forms are called the different cases of the noun, and, if you’ve never studied a language which uses cases, it takes some adjustment.

Fortunately, however, because Latin is the most popular of all of the dead languages, it’s also blessed with the most and best resources available for any of them. This is why I recommend Latin as a good first dead language.

If you’re studying as an autodidact, it’s eminently possible to make good progress with Latin. Start with Hans Ørberg’s brilliant reader Lingua Latina per se Illustrata (LLPSI). More specifically, since LLPSI is a series, start with the first instalment: Familia Romana.

One day I’ll write up a long explanation of why this book is so great. But here’s the short version: it teaches you Latin by telling a story, gradually introducing you to the vocabulary and grammar of the language as you progress through the book’s 35 chapters.

The entire book is also written in Latin, including all the grammatical explanations. But that’s not really why the book works, at least in my opinion. The real reason the book works is that you’re led gradually through the language while your mind is otherwise occupied with the story of the rich, and not altogether sympathetic, Roman aristocrat Iulius and the misadventures of the members of his household.

Most students find that Familia Romana is not itself enough to get them to authentic literature on its own, but, luckily for those students, there are many talented authors and broadcasters (sounds more dignified than Youtubers) out there creating material for Latin learners, including Luke Ranieri, Carla Hurt, Satura Lanx, and the good people at Latinitas Animi Causa.

Rating: S-Tier / Easy

2. Old English

It might surprise you to see Old English ranked as slightly harder to learn than Latin. That seems a bit weird: sure, Latin has given English a lot of vocabulary, but it’s still from a different family altogether.

Old English, on the other hand, is literally an earlier form of Modern English (well, mostly). How could it be harder to learn than Latin?

Well, Old English is deceptive. It looks easy at first, with all the familiar words: hand means ‘hand,’ hūs means ‘house,’ bera means ‘bear.’ This certainly gives a speaker of (Modern) English a leg up. Old English does require you to learn some grammatical forms — cases, verb conjugations, even grammatical gender — but far fewer than Latin. And it’s true: you only have to learn a few forms for each word.

But Old English grammatical endings are also trickier to learn than Latin equivalents, because the same endings do multiple jobs,3 making it harder to create mapping between form and meaning.

For example, -e is the dative singular ending for some nouns, the nominative singular for others, and for still others it’s the accusative singular ending. Couple that with lots of stem changes (so changing a word is also a matter of changing the internal vowel, not just adding an ending), and endings which appear or disappear depending on the shape of the root, and Old English grammar is actually in many ways harder than Latin!

But it’s definitely doable. There are pretty good resources out there. Shameless self-promotion, I wrote one of them: a progressive Old English reader called Ōsweald Bera: An Introduction to Old English. It aims to provide Old English students with a similar experience to what Lingua Latina per se Illustrata provides to students of Latin,4 teaching the language by telling a delightful (my editor asked me to say delightful) story about the misadventures of a talking bear in Anglo-Saxon England.

I actually wrote a whole post in late 2024 describing a curriculum for learning Old English, so rather than blather on here about it, I’ll send you over there.

Rating: S-Tier / Easy

3. Sanskrit

This ranking might also be controversial. Sanskrit seems like it’ll be very difficult. It’s got a different alphabet and the words are mostly unfamiliar unless you already know an Indian language (although if you do yoga, you get some words for free!). There are endings upon endings to learn, and the grammar is much more elaborate than Old English, or even Latin.

But, despite all this, Sanskrit is, in my opinion, not nearly as scary as advertised. Yes, it has a lot of forms to learn, but the forms are much more straightforward and logical than even the forms of Latin.

Because there are more forms to learn, by and large, there’s a more equitable division of labour among them: each grammatical form does one thing and one thing only. As a result, learning endings feels more like learning vocabulary than learning grammar.

Sanskrit tends to be written in the Devanagari script, which is also used today for Hindi. This is mostly a matter of convention: historically, Sanskrit has been written in a variety of scripts. But you’ll need to learn Devanagari in order to read editions of Sanskrit texts published today.

Devanagari does present a challenge, but it’s a finite one. There are lots of symbols to keep track of, but many of them are very rare. Once you’ve learned the common symbols, you can put off learning the rarer symbols for when you encounter them in words. So the writing system is more of an initial speed bump than a serious impediment.

Sanskrit also has the enormous advantage of having one of the best introductory readers available for any language, and it’s completely free. The amazing (and, as far as I know, anonymous) team behind the Amarahasa project have written a sequence of easy Sanskrit stories, similar to Familia Romana or Ōsweald Bera, although unlike these books, Amarahasa stories are primarily adaptations of popular Sanskrit texts, such as the Ramanaya, Bhagavad Gita, and Buddhacarita (‘Acts of the Buddha’), told and retold at various levels of difficulty.

I can’t recommend Amarahasa enough. It, even more than Familia Romana, was one of the inspirations for Ōsweald Bera. Couple that with grammar guides either from Learn Sanskrit or the University of British Columbia Sanskrit programme and you’ll be able to enter into the vast and beautiful world of Sanskrit literature: a world that few in the English-speaking world know very much about.

Rating: A-Tier / Fine

4. Old Norse

Old Norse is closely related to Old English: both are medieval Germanic languages, and, as such, the two have a lot in common, not just grammatically but also culturally. So everything I’ve said about the intrinsic difficulty of Old English applies to Old Norse as well.

The big difference between the two of them is that, with Old Norse, everything is just a little bit more challenging. The words are less recognizable, there are more grammatical forms to learn, and there are more crazy stem changes to keep track of. It feels like learning Old English on hard mode.

But the rewards are, if anything, greater. The subject matter of Old Norse prose is — for most modern readers — more intrinsically interesting than the things the Anglo-Saxons wrote about. Old English prose tends to deal in saints’ lives and homilies. These are interesting to some, but to most they can be a bit of an acquired taste.

Old Norse prose, on the other hand, has the sagas, accounts of the doings of legendary heroes and villains, multigenerational feuds between Icelandic chieftains, and fights with supernatural monsters. Most readers don’t need to train their taste to like this material.

The great difficulty with Old Norse is the resources, or rather, the lack thereof. I don’t mean to suggest that there are no good resources. In fact, there are many good explanations of Old Norse grammar around, such as from the UT Austin’s Linguistics Research Centre, P. S. Langeslag’s guide to Old Norse grammar, and Jackson Crawford’s Old Norse video course.

But there is, to date, no easy reader of Old Norse — at least, not to my knowledge. The best place, therefore, to start is with Jesse Byock’s student editions of sagas: Þorsteins þáttr stangarhǫggs and Vápnfirðinga saga. These are great: they gloss all words, give you grammatical help, and include essays explaining cultural context. Everything you’d want in an intermediate reader.

The problem is that you need to start with the intermediate reader, and it can be painful to do so without a large enough vocabulary and basic model of the grammar already in your mind. Reading these texts as a beginner is a halting experience, as you have to look up almost every word and new grammatical form.

It is possible to make progress this way (I know from experience) but I don’t recommend it, not unless you’ve already studied another ancient language and know how the process goes under more ideal circumstances. Also, Old English helps so much with Old Norse — and is so much easier to learn — that I would recommend prospective students of Old Norse start there, and gain at least an intermediate level in Old English before proceeding to Old Norse.

Rating: A-Tier / Fine

5. Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek is probably the second-most popular ancient language to study, and it’s not hard to understand why. It’s the original language of three of the most important texts (or collections of texts) in the history of the Western world: Homer, Plato, and the New Testament. And that is just scratching the surface.

Unfortunately, all of that richness is locked behind a challenging grammar. In fact, I believe that Ancient Greek has the hardest grammar to master of any Indo-European language that I have studied.5 The weird thing is that the grammatical system is basically the same as that of Sanskrit. But, in my experience at least, it feels a lot less intuitive.

One example of the trickiness of Ancient Greek is that there is (in Attic, at least, which is the dialect you learn from textbooks and classes) a system of vowel contractions, where two vowels appearing side by side change into another vowel by a complex series of rules.

For example, ε + ο = ου (or, in Roman letters, e + o = ū). This sort of thing happens in Sanskrit as well, but the combinations there make a lot more sense, to me at least. You more than occasionally have to mentally undo these contractions in order to know how to use a word.

I don’t mean to use this section to complain about Ancient Greek. It’s been around a lot longer than I have, and it’s earned the right to have whatever grammar it wants.

You may even find Ancient Greek grammar relatively manageable. But the difficulty of Ancient Greek isn’t just in its grammar: it’s in the combination of the grammar with the resources available for learners. Unlike Old Norse, there are actually quite a few easy readers out there for Ancient Greek, for example, Athenaze, Logos, and Thrasymachus.

These readers are intended to be easy. In practice, however, they are fairly hard. At least, they’re much harder than Familia Romana is for most Latin learners (and even that is no walk in the park).

Even though each of them is a great resource, and their authors deserve a lot of praise for making Greek as accessible as they have, no reader on the market truly makes things easy for beginners. A lot of effort is still required, and the pathway up the mountain is steep and occasionally rocky.

Greek requires some fortitude, so I would advise interested students to consider trying Latin first, and getting used to studying an ancient language in a more forgiving environment before tackling Ancient Greek.

Now we come to the end of the Indo-European languages on this list. The final two languages are entirely unrelated to any of the previous languages (as far as we know…). They both work very differently from the languages we’ve talked about so far, grammatically speaking, at least. This makes them harder but all the more rewarding. But proceed with caution if you’re a beginner to language learning.

Rating: B-Tier / Moderate

6. Biblical Hebrew

It’s not really correct to call Biblical Hebrew a dead language, but I hope you’ll forgive my speaking loosely.

I won’t sugar-coat it: Biblical Hebrew is a very difficult language. As a Semitic language, the way its grammar works is very unlike the Indo-European languages we have been discussing so far.

Words do change to express different grammatical categories, but these categories are marked by changes within the words rather than (or in addition to) adding different endings.

This situation is similar to what happens with Old English and Old Norse, where grammatical information is frequently expressed by changing the vowel. Even Modern English does this to a certain extent: compare the present tense sing with the past tense sang.

Biblical Hebrew elevates these internal vowel changes to an art form: basically every verb works this way in Hebrew (as do many nouns), which means that learning a word is not just a matter of learning a word. You also need to learn the various patterns of vowel changes that the word is subject to.

This makes things, in a word, hard. The difficulty is compounded by the fact that you’ll have to learn a new writing system, which is not the end of the world, but it’s written from right to left, which takes some getting used to for your brain (or, at least, my brain felt that way).

Making your life as a student even more difficult is the fact that there are few resources available for Biblical Hebrew which have been made using modern paedagogical methods. One resource that is informed by second language acquisition research, and which many students report benefiting from, is the Youtube channel Aleph with Beth,6 which slowly and gradually introduces Biblical Hebrew grammar through comprehensible input-style videos.

The best textbook out there is Lily Kahn’s The Routledge Introductory Course in Biblical Hebrew. It deals with Biblical Hebrew grammar in a comprehensive way, and even includes short graded reader-style compositions to help ease the reading burden. But this is still very much a grammar reference book, and it gets you into lots of complicated details and technical terminology right away.

What you might consider doing is learning Modern Hebrew first: it has the benefit of being a spoken language, and — while people debate just how close Modern Hebrew is to Biblical Hebrew, sometimes quite angrily — the two are certainly close enough for the one to benefit the other.

Rating: C-Tier / Hard

7. Classical Chinese

If you’re not familiar with Classical (or Literary) Chinese, it’s the form of Chinese which has served as a literary language for China and much of East Asia for over two millennia, similar to the position which Latin held in Europe until fairly recently. In fact, it’s more of a stretch to call Classical Chinese a “dead language” than the prior cases, since Classical Chinese phrases and idioms are commonly found as part of the formal register of modern written Chinese.

Classical Chinese is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the language in which the Chinese classics are written, including the Analects of Confucius, the Tao Te Ching of Laozi/Lao-tzu, and The Art of War of Sunzi/Sun-tzu, to mention the three most famous texts. It’s also the language of the great poetry of Li Bai and Du Fu.

In fact, there is so much written in Classical Chinese that to learn it is to open a door to a library which you will never exhaust in a lifetime of reading. As you may be able to glean from this description, Classical Chinese is a great love of mine, even though I’m far from an expert in it, despite a long period of study.

Like Biblical Hebrew, the language is extremely interesting grammatically for someone more used to Indo-European languages. Words do not change in any way to express any grammatical category whatsoever:7 composing sentences is strictly a matter of putting one word after another.8

By characters, I mean the characters of the Chinese writing system: 山有人, etc.9 And this brings us to another point. In its origin, Classical Chinese is the written form of Old Chinese, which was the spoken language of the central plains of China in the 1st millennium BC. The reconstruction of this spoken language is extremely challenging, due to the fact that the writing system, Chinese characters, represents sound only indirectly if at all.

So the convention is to recite Classical Chinese by saying the characters in their modern Mandarin pronunciation. So, for example, even though the character 山 ‘mountain’ is reconstructed in Old Chinese as *s-ŋrar (don’t try to pronounce it; you might summon an elder god by accident),10 most people will pronounce 山 in Classical Chinese texts the way it’s pronounced in a modern language, such as Mandarin shān.

Today, the language chosen to pronounce the characters in is Mandarin, but, in theory, you could pronounce Classical Chinese in Cantonese, Japanese, Korean, or any other language which uses (or has used) Chinese characters.

But, unfortunately, all modern languages have merged a lot of the sounds that Old Chinese would have kept separate, so, as a result, you end up not being able to distinguish between different characters. The result is poems such as Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den, in which every character is pronounced in Mandarin as shi (or occasionally si or she).11

This means that there isn’t really (to my knowledge) a tradition of speaking Classical Chinese like there is for Latin or Ancient Greek. This is a shame because the ability to speak ancient languages, and listen to them spoken, helps immensely with one’s ability to read and write them.

All of this — not to mention the fact that you have to learn Chinese characters, and none of the words have any relationship to anything you already know12 — is why Classical Chinese is difficult for English speakers.

To top it off, there are comparatively few resources available in English. But, nevertheless, few does not mean none: Bryan Van Norden has written an excellent beginner textbook Classical Chinese for Everyone. This explains much of the grammar of Classical Chinese and gives you some short passages to read. But you will not be an independent reader by the end of it. Instead, you might be able to progress to other introductory textbooks such as Rouzer or Fuller. If you’re interested in poetry, Archie Barnes’ textbook Chinese through Poetry (the official website is down, but it’s easily findable) is also a good choice.

Honestly, you’ll probably need to use all of them.

For grammar reference, the students of the same Archie Barnes have compiled their notes into Du’s Guide to Classical Chinese Grammar, which is a good concise reference. Edwin Pulleyblank’s Outline of Classical Chinese Grammar is less user-friendly, but more complete.

In any case, you’re not going to have an easy time. My advice would be to learn Modern Mandarin first, at least to an intermediate level, before tackling Classical Chinese. This will lighten the burden of learning the characters, and you’ll be able to access some of the resources out there written in Modern Chinese.

Rating: D-Tier / Insane

Conclusion

I hope I haven’t scared you off learning whatever language has piqued your interest! The truth is: if you want to make learning ancient languages part of your life, there’s never been a better time to do it.

Each one of the seven languages I mentioned has more, and better, resources coming out to help learners year after year. So even if you’re looking at the hardest of the hard languages, you can succeed. Just remember the principles of language learning, gird yourself appropriately, and go forth!

Image credits for tier list: Latin: The Capitoline Wolf (CC0, Wilfredor), Old English: Replica of the Sutton Hoo Helmet (CC BY-SA 3.0, Ziko-C), Sanskrit: Scene from the Ramayana, Old Norse: Mjǫlnir (CC BY 4.0, Ola Myrin, Statens historiska museum/SHM - The Viking World), Ancient Greek: Parthenon (CC BY 2.0, Steve Swayne), Biblical Hebrew: Caves at Qumran (CC BY-SA 2.5, Tamarah), Classical Chinese: Shi Jing.

I should say “historical language” rather than “dead language” but then I’d have to change the name of this newsletter, which is just too perfect as it is.

This phenomenon, called morphological syncretism, happens a little bit in Latin: for example, the single form puellae could mean ‘for the girl,’ ‘of the girl,’ or ‘girls’ (in the nominative case, at least). But morphological syncretism is much more extensive in Old English.

There are, however, some differences in the pedagogical philosophy between Ōsweald Bera and the Lingua Latina per se Illustrata series. But in the grand scheme of things, they’re minor. Both books aim to get you lots of easy reading and try to make the difficulty slope as gentle as possible.

It should be noted that I have not studied Old Irish, which is famous for its perversely difficult grammar. I have no doubt that it is as bad as advertised, but I’ve limited this list to languages which I have some experience studying.

A warning: I can’t mention Aleph with Beth without mentioning that the hosts do pronounce the Tetragrammaton, which will disqualify this resource for many students.

Actually, it’s a little more complicated than this. There probably were some grammatical affixes in Old Chinese, the spoken language which forms the basis of Classical Chinese.

Technical note: the concept of word is not totally ideal here. For one thing, there are no word boundaries in the writing system. It’s just one character after another. Word is not a universal category, anyway, so don’t worry about it too much. Most of the time, Classical Chinese is thought of in terms of sequence characters, which are more or less the same thing as morphemes (pairings of sound and meaning). This is also not totally ideal, since some characters write multiple morphemes. It’s a bit tricky but you’ll get used to it.

By the way, that’s a valid Classical Chinese phrase meaning ‘in the mountain there was a person’.

This is in the Baxter-Sagart reconstruction, for the record.

Some characters are, of course, distinguished by different tones. This helps, but less than you might think.

Unless you already know a modern Chinese language (or Korean, Japanese, or Vietnamese).

Wow, this article really came at an interesting moment in my life; I just started learning a dead language myself.

Ge'ez (Classical Ethiopic) was a language used in the Axumite Kingdom in the Horn of Africa. Even though it "died" a 1000 years ago or so, it lived on in the writings of the literate. Now it mostly survives as the liturgy language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. It is somewhat like Latin in that regard.

Your point about the need for a beginner-friendly reader is sorely felt. Smashing one's head against a grammar, a dictionary, and a text with little to show for it does get dull after a while. I sometimes wonder if, whenever I get good enough at it, I should work on a reader that incorporates modern pedagogy into the language.

I am lucky enough to speak a closely related language, though, so it is not all bad. I am sure it was much more difficult for the Europeans who tried to study it. I am encouraged by (and grateful for) the fact that not only did they succeed, they also wrote a bunch of very helpful grammars and dictionaries.

Glad to know that I've mastered the second hardest language on your list.

Hebrew is my best foreign language so I'm not the best judge. I'm close to conversationally fluent and can read everything from the Bible to modern novels (although Isaiah, Job and the works of Amos Oz require that I keep dictionary close at hand). A few things:

1) Modern Hebrew vs Ancient Hebrew: As a practical matter, a speaker of modern Hebrew can read the majority of the bible. To compare to English, some of it's like reading an 18th century novel, some like Shakespeare, some like Chaucer. Nothing's like Beowulf.

2) When you learn modern Hebrew in Israel, you learn without vowels. Which means you learn the patterns. I've met lots of folks learning Biblical Hebrew who rely on the vowels and never get the patterns

3) Unlike any language on your list, Hebrew offers full immersion opportunities that no Latin conventiculum can match.

3) for me, the challenges of Hebrew and Latin are exactly opposite.

After learning Hebrew, Latin vocabulary feels like a gimme. Hebrew to English cognates? You'll have to wait for the next Jubillee. (Mammon, meaning property as in "my stuff" is found in rabbinic hebrew, originally from Aramaic). Indeed, when I tried some ancient greek, I was like "wow, look at all these cognates"

Hebrew syntax is way, way simpler. Probably why the vulgate is a good intermediate text as Jerome mimics the the simpler sentence structure.

If I ever get to Greek, I may take a month in Greece just to get a feel for the language, noting that my first interests are more Koine (septuagint) than classical.